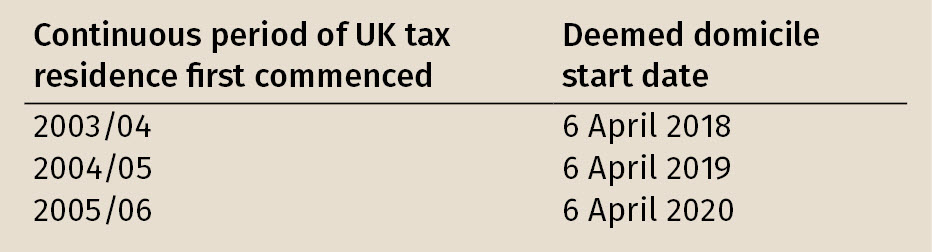

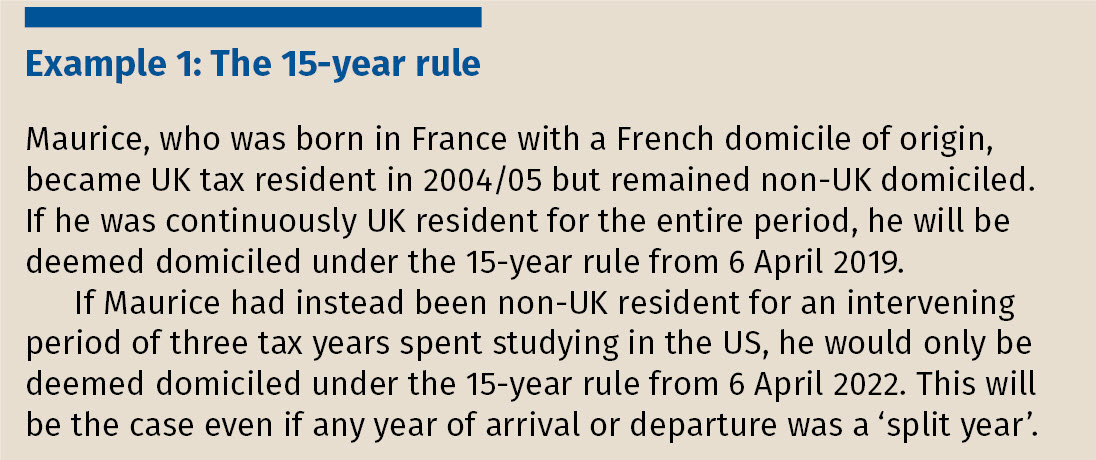

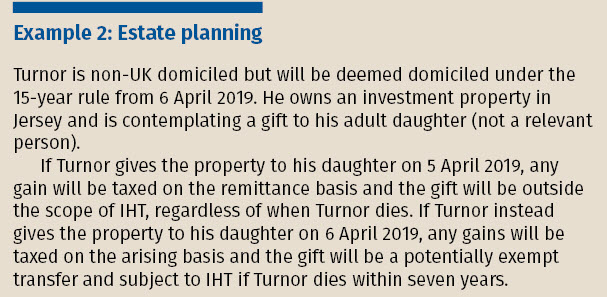

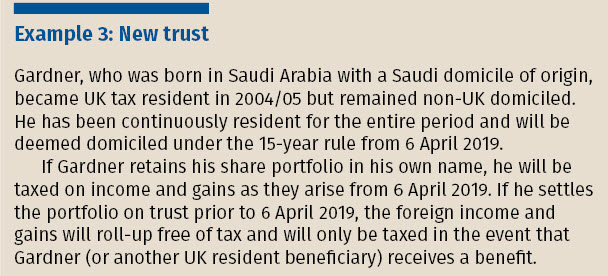

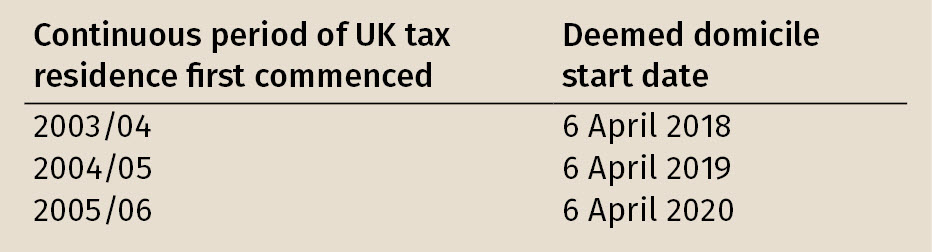

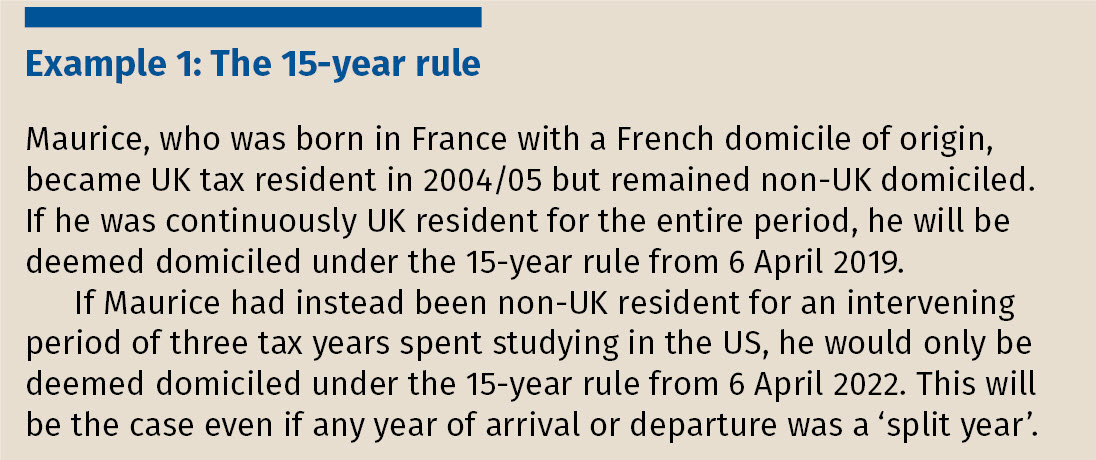

Following changes to the rules in April 2017, non-domiciled individuals who have been tax resident in the UK for 15 out of the preceding 20 tax years are ‘deemed domiciled’ for UK income tax, capital gains tax and inheritance tax purposes. The tax implications of being deemed domiciled can be mitigated by appropriate planning in the preceding tax year(s). The use of offshore trusts is particularly beneficial, provided the trusts are settled and operated in accordance with the strict legislative conditions.

Emma-Jane Weider and Claire Weeks (Maurice Turnor Gardner) focus on those UK resident individuals who are non-UK domiciled but who will become ‘deemed domiciled’ for tax purposes from the start of the 2019/20.

Acceleration of income receipts and capital gains

Following changes to the rules in April 2017, non-domiciled individuals who have been tax resident in the UK for 15 out of the preceding 20 tax years are ‘deemed domiciled’ for UK income tax, capital gains tax and inheritance tax purposes. The tax implications of being deemed domiciled can be mitigated by appropriate planning in the preceding tax year(s). The use of offshore trusts is particularly beneficial, provided the trusts are settled and operated in accordance with the strict legislative conditions.

Emma-Jane Weider and Claire Weeks (Maurice Turnor Gardner) focus on those UK resident individuals who are non-UK domiciled but who will become ‘deemed domiciled’ for tax purposes from the start of the 2019/20.

Acceleration of income receipts and capital gains