The current paper stamp duty regime is outdated in today’s digital age, often resulting in practical frustrations. To address these issues, and pave the way for wider reform, the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) is proposing a package of measures to digitise paper stamp duty (replacing stamping machines with an online submission system), amending company registrars’ legal obligations, making stamp duty an assessable tax and aligning its scope more closely with SDRT.

The scope of paper stamp duty has been reduced dramatically since its inception in 1694, most notably in 1986 when stamp duty reserve tax (SDRT) was introduced for the majority of (on-market) share transactions, and then in 2003 when transactions in land were taken out of stamp duty in favour of stamp duty land tax (SDLT).

As a result, there are now only a limited range of circumstances in which physical documents are stamped. This is reflected in the total stamp duty yield on shares collected in 2015/16 (£700m), which was significantly less than SDRT yield in the same period (£2,600m).

The physical stamping process is slow, which can cause particular frustrations where there is a commercial imperative to register a transaction on the same day that it is carried out.

HMRC aims to process straightforward stock transfer forms within five working days, and more complex applications (such as claims for reliefs) within 15 working days. These targets were, however, met in only 70% of cases in 2016/17, so in that year over 30,000 documents were received by taxpayers after longer periods than this. Delays can be caused by documents going astray in the post, having to be sent back unstamped because of a mistake on the document, or needing to be returned because of difficulties in matching up payments with the documents concerned.

These potential delays can cause time consuming and costly frustration for taxpayers, especially in relation to urgent transactions where there is a need for a share transfer to be registered on the same day as the transaction. The market has devised various ‘work-arounds’ to address this, but the overwhelming feedback we received was that it would be much better to find an alternative solution. The present position is sometimes said to be a blemish on the UK’s reputation as a modern financial centre, as well as inhibiting technological developments such as digital signatures.

It is in this context that the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) has carried out a review to find ways to simplify paper stamp duty. The review was project managed by Olimpia Wojtyczko, supported in particular by Daphna Jowell. We have held over 60 meetings with advisers and professional bodies, as well as HMRC, HM Treasury, BEIS and Euroclear UK & Ireland. A progress report was published in March, outlining our initial findings and calling for further evidence. Following further meetings, discussions with a consultative committee and reviewing written submissions and responses to an online survey, our final report was published in July 2017.

Broadly speaking, those we spoke with raised three issues: the administrative process of stamping a document (as discussed above); technical issues with the existing legislation (such as its territorial scope); and the possibility of a full alignment or integration with SDRT.

Generally, those respondents who were involved in complex, time critical transactions wanted to see an immediate change. Those who tended to deal with more straightforward, non-urgent transactions did not advocate any major changes to the system, although they would still welcome a reduction in processing glitches, such as documents lost in the post.

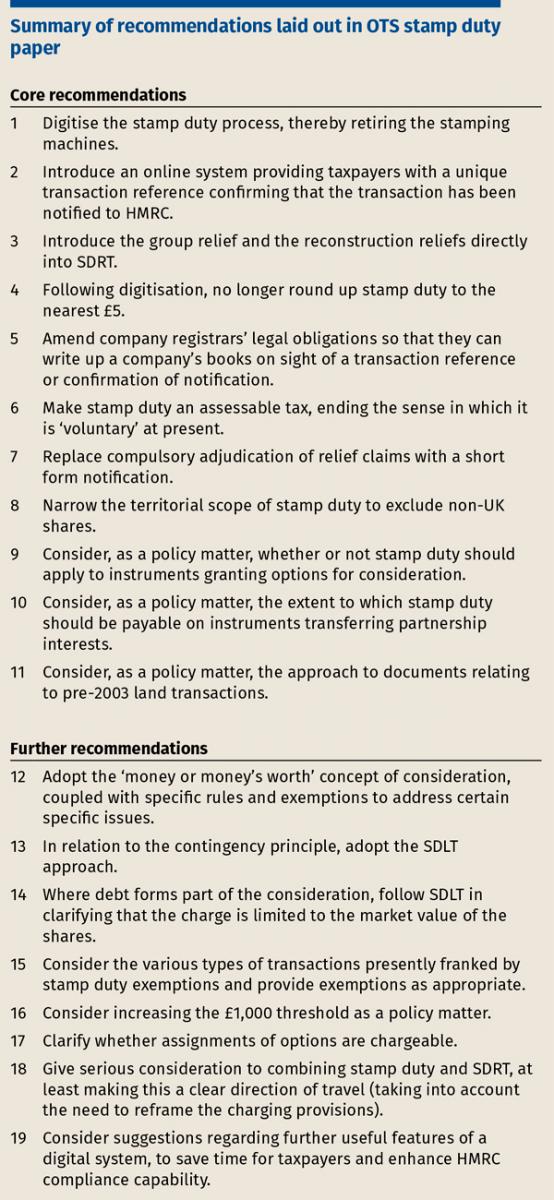

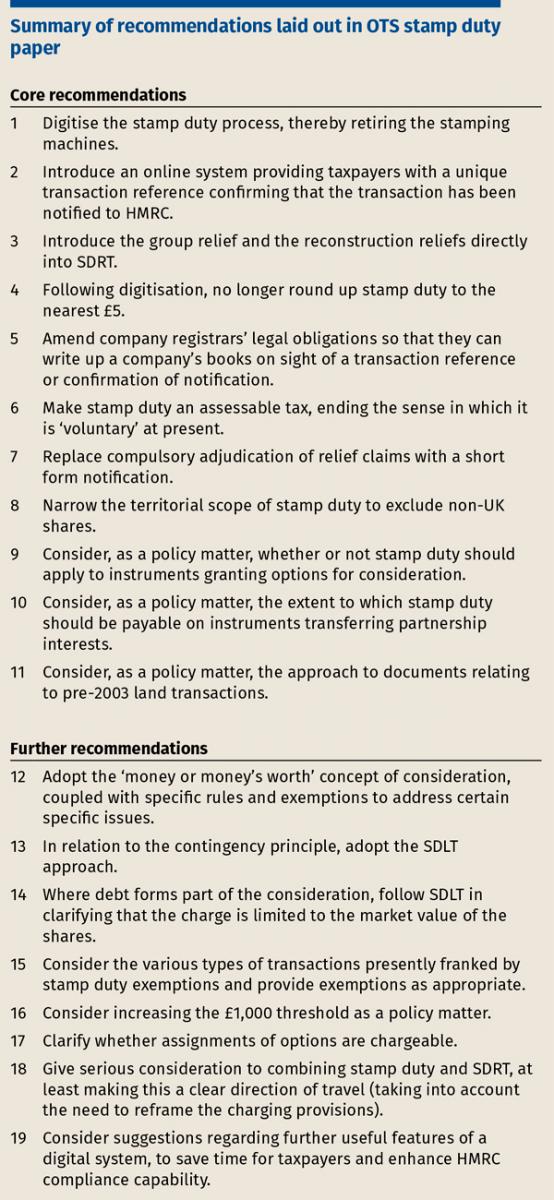

The OTS’s response to this is to recommend a set of interdependent core recommendations to address the most pressing issues, alongside further recommendations for simplification.

1. Introduce a digitised system and retire the stamping machines

The first recommendation is to introduce a digitised system and retire the stamping machines. The report makes a number of suggestions about the desirable features of a digitised system but, at its simplest, this would involve allowing a scanned version of the transfer instrument to be uploaded. A unique transaction reference (UTR) number would then be issued, serving as confirmation that the transaction has been notified to HMRC.

Together with the original transfer instrument, the UTR could be presented to registrars to allow them to write up the company’s shareholder register. It could also be used as a reference number when making the stamp duty payment.

There are many benefits of digitisation, such as round-the-clock availability, convenience and improved security.

Currently, registrars may be subject to a fine if they update a register in the absence of a stamped, or exempt, transfer instrument. So digitising the process for paying stamp duty would not be enough, by itself, to address business concerns about being able to see company registers being updated on the same day as the transaction.

2. Amend the company registrars’ legal obligations

The second recommendation is to amend the company registrars’ legal obligations, allowing them to write up a company’s books on sight of a UTR or some other confirmation of notification to HMRC. This would allow the same day registration of share ownership. (This recommendation could also be implemented by itself as a simple and effective first step towards implementing the core recommendations, in situations where HMRC already has recourse to an SDRT charge to ensure payment.)

Digitisation means HMRC would no longer have the ability to check that the correct amount of tax has been paid before issuing the UTR. So HMRC would need powers to enforce payment, along the lines of those used in SDLT, effectively ending the ‘voluntary’ nature of stamp duty.

3. Make stamp duty an assessable tax

Accordingly, our third recommendation is to make stamp duty an assessable tax, with the transferee being the person legally responsible for payment.

This has a number of potential advantages, including enabling HMRC to operate a risk assessment approach, focusing its review work on higher risk transactions and replacing compulsory adjudication of stamp duty relief claims with a short form notification.

This is particularly relevant to the most commonly applied for group relief and the reconstruction reliefs (FA 1930 s 42 and FA 1986 ss 75 and 77), which we recommend are introduced directly into SDRT. This would align the two taxes in this respect and eliminate the need to create a paper transfer instrument purely in order to be able to claim a relief when transferring shares in CREST.

4. Narrow the territorial scope of stamp duty

Following on from making stamp duty assessable, our fourth recommendation is to simplify the scope of stamp duty, aligning its scope with SDRT, so that it can work appropriately. In particular, we recommend narrowing the territorial scope of stamp duty so that non-UK shares are clearly excluded. To this end, we suggest adopting the full SDRT definition of chargeable securities, as it would have the simplifying effect of bringing the bases of the two taxes into closer alignment.

We also suggest that the policy in relation to documented option grants is considered, along with that concerning transfers of partnership interests, and documents relating to pre-2003 land transactions. Even if no other changes are made, making stamp duty an assessable tax could lead to behavioural change or an increase in the amount of tax collected. So although at present, for various reasons, very few such instruments are submitted for stamping each year, policy in these areas needs to be reviewed.

The second part of our report addresses a number of specific technical issues, and the possibility of combining stamp duty with SDRT. It also touches on more advanced features that the digital system should, in our opinion, include to provide the best customer experience.

The main technical issue discussed in this section is the definition of consideration for stamp duty and SDRT. The SDRT definition of consideration (‘money or money’s worth’) is broader than stamp duty’s, which includes only cash, stock or marketable securities, and debt. We recommend adopting the SDRT definition for stamp duty purposes, aligning the taxes. However, this needs to be coupled with additional rules and exemptions to address certain specific issues:

First, with regard to contingent, uncertain and unascertained consideration, simply adopting the SDRT concept of consideration could mean the unknown part of the consideration would need to be valued at the date of the transaction, to determine the value of the ‘money’s worth’ part of the consideration. That’s clearly not a simplification. Therefore, we recommend adopting the SDLT approach where, while consideration is defined to be money or money’s worth, further specific provisions are included to address the position of unknown or uncertain consideration.

Second, where debt forms part of the consideration, we recommend that the stamp duty rules are clarified so that the charge is limited to the market value of the shares, as with SDLT.

Finally, there are a number of types of transaction which, when carried out in paper form, fall outside the narrower stamp duty definition of consideration. Such transactions include contributions to a partnership in return for a membership interest, and distributions in specie out of a partnership in return for a redemption of partnership capital. Specific provisions would be required to preserve the present position if the money or money’s worth definition of consideration is adopted. We recommend that these are reviewed and specific exemptions are implemented if required.

Another technical issue we consider is the exemption from stamp duty where the consideration is under £1,000. Given the nature of the transactions covered by the £1,000 exemption (e.g. transfers of shares between family members for a low value), we believe removing it would impose an undue burden, especially on individuals. Therefore, we recommend it is retained, and that the possibility of increasing it is considered. We also suggest the threshold is retained for non-CREST transactions, if stamp duty and SDRT are combined.

Combining stamp duty with SDRT

As regards the possibility of combining stamp duty with SDRT under a single ‘umbrella’, we heard strongly held views both for and against.

Our report suggests this should be the broad ‘direction of travel’ and that any changes to stamp duty should be made in a way which facilitates this. We also set out some ideas on how a combined tax might work; in particular, on how best to combine the charging provisions.

For a combined tax to work, it would need to address all the situations where franking is presently relied on to work around the fact that not all stamp duty reliefs are available in SDRT, but this would in any case be a natural part of bringing the two taxes together. Changes to integrate the taxes would also assist in resolving situations where a double charge, to both SDRT and stamp duty, can arise at present.

Even if stamp duty is not combined with SDRT, we suggest the franking provisions are reviewed to ensure that only one charge can arise per transaction. In addition, consideration should be given to ensuring that no SDRT charge arises where a contract does not complete, there being no substantial performance, by analogy with the SDLT rules.

The final section of the report lists a number of more advanced features that the online stamp duty system should have to make the most of the new, digitised stamp duty. The two key features are an online return (similar to an SDLT return), so that documents wouldn’t need to be posted or even scanned; and an easy and secure online payment system (to stop the ‘transaction to payment’ matching issues).

Taken as a whole, our proposed package of recommendations, some of which could be progressed sooner than others, would represent a thorough modernisation of the UK’s oldest current tax and facilitate the same day registration of share transactions where desired.

The author thanks his OTS colleagues Olimpia Wojtyczko and Daphna Jowell for their contribution to this article.

The current paper stamp duty regime is outdated in today’s digital age, often resulting in practical frustrations. To address these issues, and pave the way for wider reform, the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) is proposing a package of measures to digitise paper stamp duty (replacing stamping machines with an online submission system), amending company registrars’ legal obligations, making stamp duty an assessable tax and aligning its scope more closely with SDRT.

The scope of paper stamp duty has been reduced dramatically since its inception in 1694, most notably in 1986 when stamp duty reserve tax (SDRT) was introduced for the majority of (on-market) share transactions, and then in 2003 when transactions in land were taken out of stamp duty in favour of stamp duty land tax (SDLT).

As a result, there are now only a limited range of circumstances in which physical documents are stamped. This is reflected in the total stamp duty yield on shares collected in 2015/16 (£700m), which was significantly less than SDRT yield in the same period (£2,600m).

The physical stamping process is slow, which can cause particular frustrations where there is a commercial imperative to register a transaction on the same day that it is carried out.

HMRC aims to process straightforward stock transfer forms within five working days, and more complex applications (such as claims for reliefs) within 15 working days. These targets were, however, met in only 70% of cases in 2016/17, so in that year over 30,000 documents were received by taxpayers after longer periods than this. Delays can be caused by documents going astray in the post, having to be sent back unstamped because of a mistake on the document, or needing to be returned because of difficulties in matching up payments with the documents concerned.

These potential delays can cause time consuming and costly frustration for taxpayers, especially in relation to urgent transactions where there is a need for a share transfer to be registered on the same day as the transaction. The market has devised various ‘work-arounds’ to address this, but the overwhelming feedback we received was that it would be much better to find an alternative solution. The present position is sometimes said to be a blemish on the UK’s reputation as a modern financial centre, as well as inhibiting technological developments such as digital signatures.

It is in this context that the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) has carried out a review to find ways to simplify paper stamp duty. The review was project managed by Olimpia Wojtyczko, supported in particular by Daphna Jowell. We have held over 60 meetings with advisers and professional bodies, as well as HMRC, HM Treasury, BEIS and Euroclear UK & Ireland. A progress report was published in March, outlining our initial findings and calling for further evidence. Following further meetings, discussions with a consultative committee and reviewing written submissions and responses to an online survey, our final report was published in July 2017.

Broadly speaking, those we spoke with raised three issues: the administrative process of stamping a document (as discussed above); technical issues with the existing legislation (such as its territorial scope); and the possibility of a full alignment or integration with SDRT.

Generally, those respondents who were involved in complex, time critical transactions wanted to see an immediate change. Those who tended to deal with more straightforward, non-urgent transactions did not advocate any major changes to the system, although they would still welcome a reduction in processing glitches, such as documents lost in the post.

The OTS’s response to this is to recommend a set of interdependent core recommendations to address the most pressing issues, alongside further recommendations for simplification.

1. Introduce a digitised system and retire the stamping machines

The first recommendation is to introduce a digitised system and retire the stamping machines. The report makes a number of suggestions about the desirable features of a digitised system but, at its simplest, this would involve allowing a scanned version of the transfer instrument to be uploaded. A unique transaction reference (UTR) number would then be issued, serving as confirmation that the transaction has been notified to HMRC.

Together with the original transfer instrument, the UTR could be presented to registrars to allow them to write up the company’s shareholder register. It could also be used as a reference number when making the stamp duty payment.

There are many benefits of digitisation, such as round-the-clock availability, convenience and improved security.

Currently, registrars may be subject to a fine if they update a register in the absence of a stamped, or exempt, transfer instrument. So digitising the process for paying stamp duty would not be enough, by itself, to address business concerns about being able to see company registers being updated on the same day as the transaction.

2. Amend the company registrars’ legal obligations

The second recommendation is to amend the company registrars’ legal obligations, allowing them to write up a company’s books on sight of a UTR or some other confirmation of notification to HMRC. This would allow the same day registration of share ownership. (This recommendation could also be implemented by itself as a simple and effective first step towards implementing the core recommendations, in situations where HMRC already has recourse to an SDRT charge to ensure payment.)

Digitisation means HMRC would no longer have the ability to check that the correct amount of tax has been paid before issuing the UTR. So HMRC would need powers to enforce payment, along the lines of those used in SDLT, effectively ending the ‘voluntary’ nature of stamp duty.

3. Make stamp duty an assessable tax

Accordingly, our third recommendation is to make stamp duty an assessable tax, with the transferee being the person legally responsible for payment.

This has a number of potential advantages, including enabling HMRC to operate a risk assessment approach, focusing its review work on higher risk transactions and replacing compulsory adjudication of stamp duty relief claims with a short form notification.

This is particularly relevant to the most commonly applied for group relief and the reconstruction reliefs (FA 1930 s 42 and FA 1986 ss 75 and 77), which we recommend are introduced directly into SDRT. This would align the two taxes in this respect and eliminate the need to create a paper transfer instrument purely in order to be able to claim a relief when transferring shares in CREST.

4. Narrow the territorial scope of stamp duty

Following on from making stamp duty assessable, our fourth recommendation is to simplify the scope of stamp duty, aligning its scope with SDRT, so that it can work appropriately. In particular, we recommend narrowing the territorial scope of stamp duty so that non-UK shares are clearly excluded. To this end, we suggest adopting the full SDRT definition of chargeable securities, as it would have the simplifying effect of bringing the bases of the two taxes into closer alignment.

We also suggest that the policy in relation to documented option grants is considered, along with that concerning transfers of partnership interests, and documents relating to pre-2003 land transactions. Even if no other changes are made, making stamp duty an assessable tax could lead to behavioural change or an increase in the amount of tax collected. So although at present, for various reasons, very few such instruments are submitted for stamping each year, policy in these areas needs to be reviewed.

The second part of our report addresses a number of specific technical issues, and the possibility of combining stamp duty with SDRT. It also touches on more advanced features that the digital system should, in our opinion, include to provide the best customer experience.

The main technical issue discussed in this section is the definition of consideration for stamp duty and SDRT. The SDRT definition of consideration (‘money or money’s worth’) is broader than stamp duty’s, which includes only cash, stock or marketable securities, and debt. We recommend adopting the SDRT definition for stamp duty purposes, aligning the taxes. However, this needs to be coupled with additional rules and exemptions to address certain specific issues:

First, with regard to contingent, uncertain and unascertained consideration, simply adopting the SDRT concept of consideration could mean the unknown part of the consideration would need to be valued at the date of the transaction, to determine the value of the ‘money’s worth’ part of the consideration. That’s clearly not a simplification. Therefore, we recommend adopting the SDLT approach where, while consideration is defined to be money or money’s worth, further specific provisions are included to address the position of unknown or uncertain consideration.

Second, where debt forms part of the consideration, we recommend that the stamp duty rules are clarified so that the charge is limited to the market value of the shares, as with SDLT.

Finally, there are a number of types of transaction which, when carried out in paper form, fall outside the narrower stamp duty definition of consideration. Such transactions include contributions to a partnership in return for a membership interest, and distributions in specie out of a partnership in return for a redemption of partnership capital. Specific provisions would be required to preserve the present position if the money or money’s worth definition of consideration is adopted. We recommend that these are reviewed and specific exemptions are implemented if required.

Another technical issue we consider is the exemption from stamp duty where the consideration is under £1,000. Given the nature of the transactions covered by the £1,000 exemption (e.g. transfers of shares between family members for a low value), we believe removing it would impose an undue burden, especially on individuals. Therefore, we recommend it is retained, and that the possibility of increasing it is considered. We also suggest the threshold is retained for non-CREST transactions, if stamp duty and SDRT are combined.

Combining stamp duty with SDRT

As regards the possibility of combining stamp duty with SDRT under a single ‘umbrella’, we heard strongly held views both for and against.

Our report suggests this should be the broad ‘direction of travel’ and that any changes to stamp duty should be made in a way which facilitates this. We also set out some ideas on how a combined tax might work; in particular, on how best to combine the charging provisions.

For a combined tax to work, it would need to address all the situations where franking is presently relied on to work around the fact that not all stamp duty reliefs are available in SDRT, but this would in any case be a natural part of bringing the two taxes together. Changes to integrate the taxes would also assist in resolving situations where a double charge, to both SDRT and stamp duty, can arise at present.

Even if stamp duty is not combined with SDRT, we suggest the franking provisions are reviewed to ensure that only one charge can arise per transaction. In addition, consideration should be given to ensuring that no SDRT charge arises where a contract does not complete, there being no substantial performance, by analogy with the SDLT rules.

The final section of the report lists a number of more advanced features that the online stamp duty system should have to make the most of the new, digitised stamp duty. The two key features are an online return (similar to an SDLT return), so that documents wouldn’t need to be posted or even scanned; and an easy and secure online payment system (to stop the ‘transaction to payment’ matching issues).

Taken as a whole, our proposed package of recommendations, some of which could be progressed sooner than others, would represent a thorough modernisation of the UK’s oldest current tax and facilitate the same day registration of share transactions where desired.

The author thanks his OTS colleagues Olimpia Wojtyczko and Daphna Jowell for their contribution to this article.