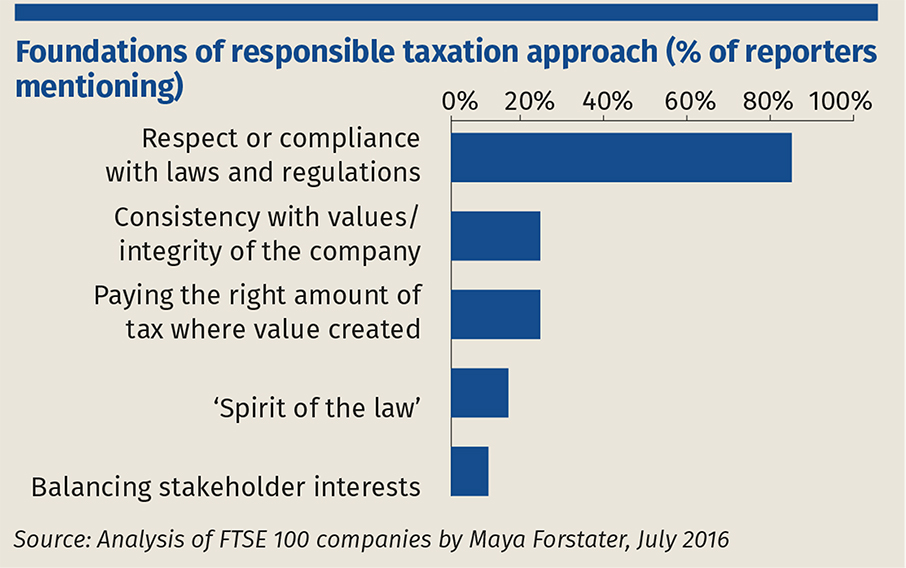

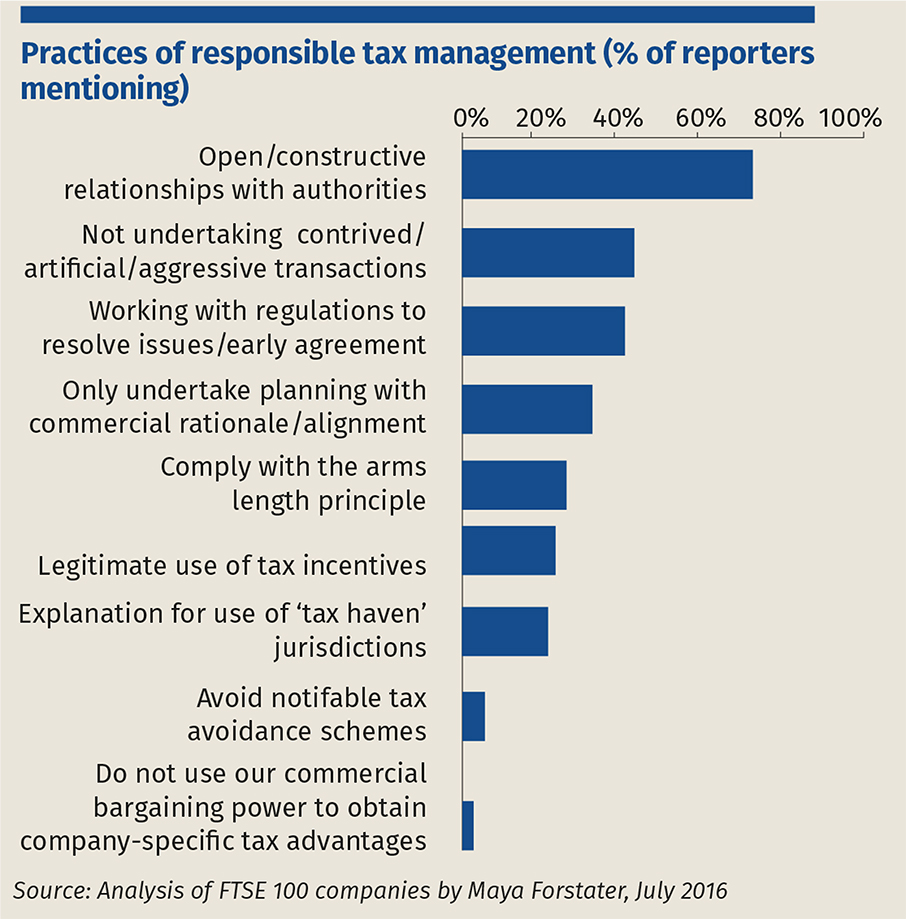

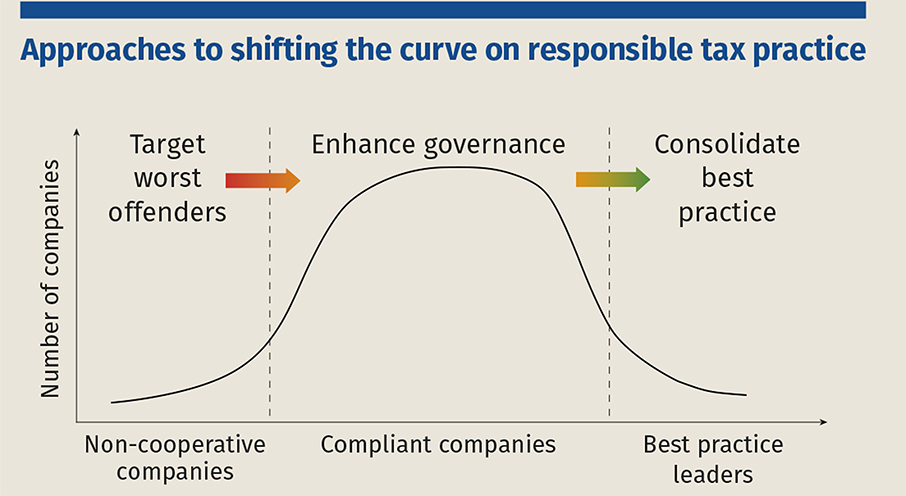

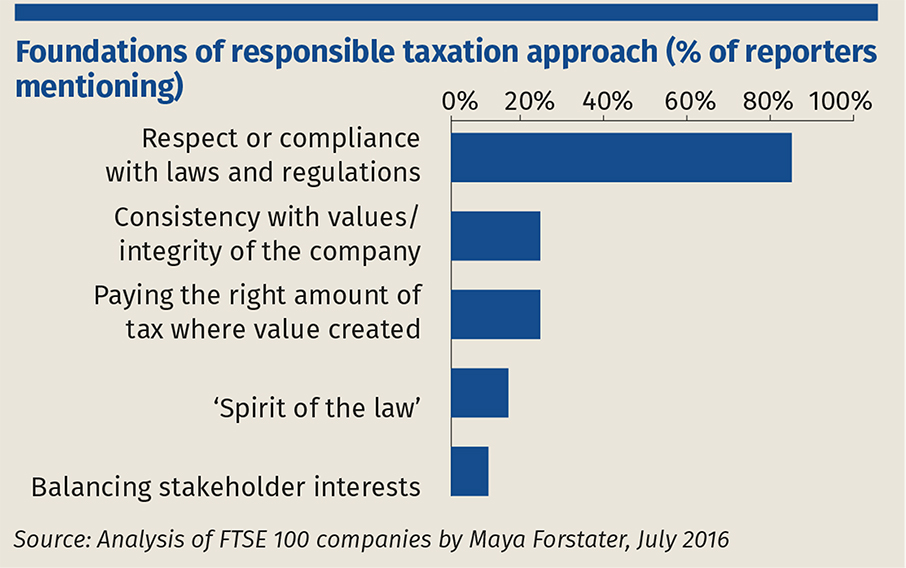

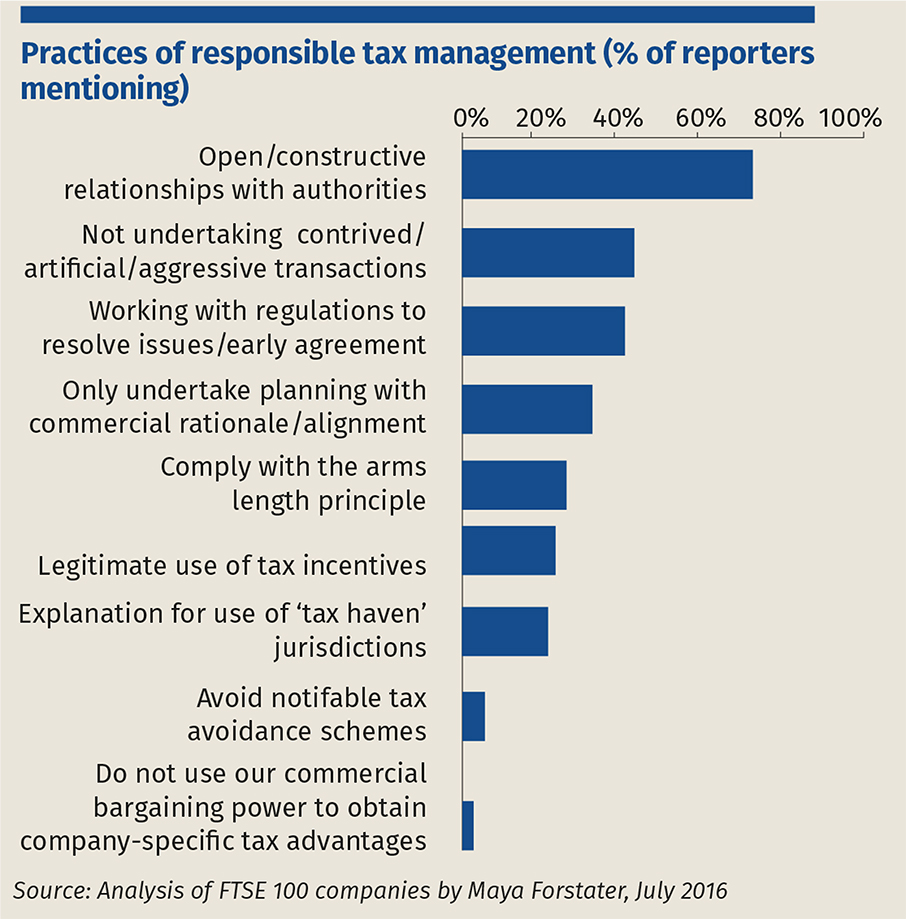

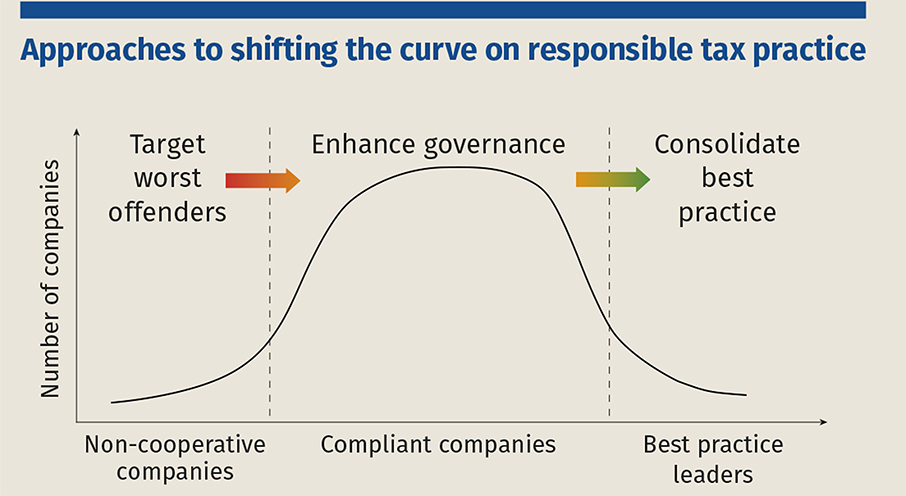

New rules will see large businesses in the UK required to publish their tax strategy. A review of statements on tax published by FTSE 100 companies to date reveals that they mainly declare (with varying levels of detail) that ‘we are doing what you would expect of a legally compliant business’. Over the next year, around 2,000 companies will need to begin publishing tax strategies. Will this make a difference to the public debate on tax avoidance and to the behaviour of individual companies, or will it only prompt a rash of bland boilerplate statements?

New rules will see large businesses in the UK required to publish their tax strategy. A review of statements on tax published by FTSE 100 companies to date reveals that they mainly declare (with varying levels of detail) that ‘we are doing what you would expect of a legally compliant business’. Over the next year, around 2,000 companies will need to begin publishing tax strategies. Will this make a difference to the public debate on tax avoidance and to the behaviour of individual companies, or will it only prompt a rash of bland boilerplate statements?