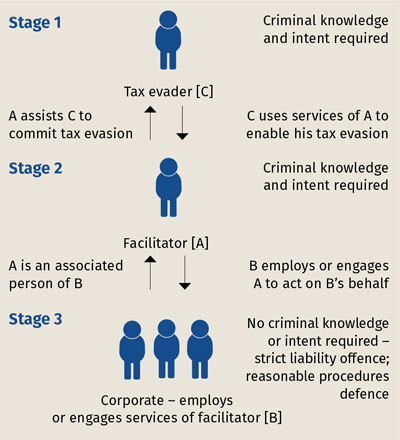

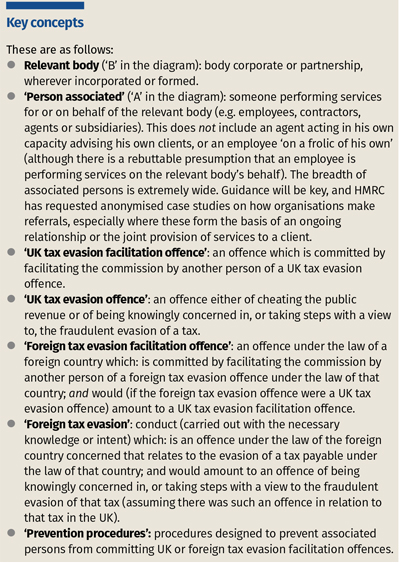

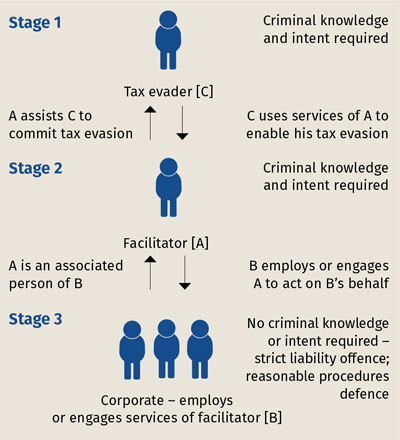

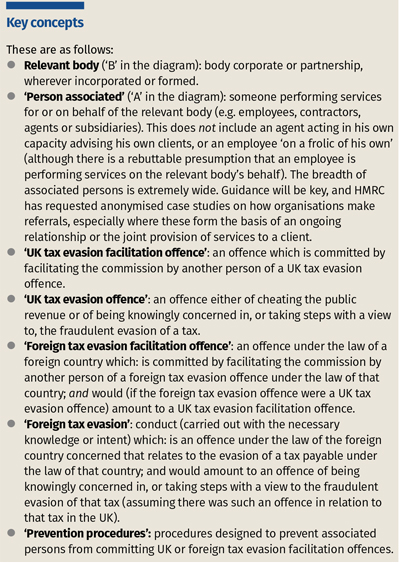

HMRC’s campaign against tax evasion will be bolstered, from autumn 2017, by a new corporate offence of failing to prevent facilitation of tax evasion. Revised draft legislation and draft guidance on the offence and related defence were published on 17 April for consultation until 10 July. The offence is loosely modelled on Bribery Act 2010 s 7. A ‘relevant body’ is guilty of the offence where a person associated with it (acting in that capacity) commits a ‘UK tax evasion facilitation offence’ or a ‘foreign tax evasion facilitation offence’. Liability is strict and no criminal intent, knowledge or condonation by senior management is therefore required.

Helen Buchanan (Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer) examines the revised draft legislation and new draft guidance on the proposed corporate offence of failing to prevent facilitation of tax evasion.

How will the offence be prosecuted?

HMRC’s campaign against tax evasion will be bolstered, from autumn 2017, by a new corporate offence of failing to prevent facilitation of tax evasion. Revised draft legislation and draft guidance on the offence and related defence were published on 17 April for consultation until 10 July. The offence is loosely modelled on Bribery Act 2010 s 7. A ‘relevant body’ is guilty of the offence where a person associated with it (acting in that capacity) commits a ‘UK tax evasion facilitation offence’ or a ‘foreign tax evasion facilitation offence’. Liability is strict and no criminal intent, knowledge or condonation by senior management is therefore required.

Helen Buchanan (Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer) examines the revised draft legislation and new draft guidance on the proposed corporate offence of failing to prevent facilitation of tax evasion.

How will the offence be prosecuted?