The UK is pushing ahead with an interest barrier, following BEPS Action 4. In addition to a fixed ratio rule and a group ratio rule, the effect of which will be to restrict UK tax deductions to a percentage of UK taxable EBITDA, the new regime includes a modified debt cap, which will further restrict deductions to the extent that they exceed the group’s net external interest costs. The rules may well affect groups that have never used BEPS strategies. The scope of what counts as qualifying debt for group ratio purposes is so narrow that even wholly UK based groups could find themselves unable to deduct all of their external interest expense.

Despite having previously resisted a ‘structural restriction’ for interest deductions – it was expressly rejected as part of the package of reforms for the taxation of foreign profits implemented a few years ago – the UK government has been quick to implement the OECD’s recommendations on BEPS Action 4 (limiting base erosion involving interest deductions and other financial payments). The basic ingredients of the new interest barrier, effective from 1 April 2017, have been well publicised: ther e is to be a fixed ratio (FR) rule, under which a group will be able to deduct net UK interest costs only to the extent that they do not exceed 30% of UK taxable EBITDA; and this is supplemented by an elective group ratio (GR) rule, pursuant to which an overall more highly leveraged group can substitute the 30% with a percentage derived from taking its group-wide third party interest expense over group-wide EBITDA.

So far, so simple, although the devil is of course in the detail. The new UK rules include some nasty tweaks to the OECD recommendations, which mean they may well restrict deductions for groups whose financing arrangements do not involve BEPS (or indeed any cross-border element). Some of the more flagrant examples of overreaching are touched on below in the course of outlining the new rules. While HMRC has already indicated that it is not likely to change its mind on certain aspects, some obvious glitches are expected to be fixed in the next version of the draft legislation. (An incomplete version was issued in December, with a full version published at the end of January for further consultation.)

The new rules will form a new Part 10 of and a new Sch 7A to TIOPA 2010. Schedule 7A will contain the administrative rules dealing with, among other things, the preparation and submission of interest restriction returns and the allocation of amounts amongst group members. Although not covered in this article, familiarity with these rules will be important in practice, including in an M&A context where companies are leaving and joining groups.

In order to operate the new rules (whether under the FR or GR method), it is necessary to identify the ‘worldwide group’ and its members, and the ‘period of account’ of that worldwide group. A worldwide group (group having the meaning given by the international accounting standards (IAS)) is constituted by the ‘ultimate parent’ and its ‘consolidated subsidiaries’. Some of these terms will be familiar from the existing worldwide debt cap (WWDC) regime, but they are in fact (subtly) different concepts.

Ultimate parent: An ultimate parent is a member of an IAS group, which is not a consolidated subsidiary of any other entity and which is:

i. a body corporate (not being a limited liability partnership or foreign entity which would be regarded as a partnership applying UK principles);

ii. an entity where the entitlement of investors to the entity’s profits is dependent on a decision taken by the entity; or

iii. an entity the shares or interests in which are listed and held by participators, none of which holds more than 10% by value.

(Determining whether condition (ii), in particular, is met is already expected to cause difficulties in practice.)

Consolidated subsidiary: A consolidated subsidiary is a subsidiary in the IAS sense which is not fair valued through profit or loss; in other words, a subsidiary which is consolidated on a line by line basis.

Period of account: This will essentially be the period in respect of which consolidated financial statements are drawn up. The interest barrier regime will operate by reference to actual or notional IAS compliant financial statements.

The companies whose financing costs are vulnerable to restriction under the new rules, and whose taxable EBITDA counts for the purposes of applying the FR and GR rules, are the UK corporation tax paying members of the worldwide group (whether UK resident or with UK permanent establishments). Very broadly – although the legislative approach to this is rather cumbersome – a company’s accounting period for corporation tax purposes will correspond to the worldwide group’s period of account to the extent the periods overlap.

‘Interest allowance’ is calculated for a period of account of a worldwide group applying the FR method; or, where a group ratio election is in place in respect of that period, the GR method. That interest allowance, taken together with any unused interest allowances from the previous five years, then represents the ‘interest capacity’ of the worldwide group for the period. This is the cap on UK tax deductions for financing costs for that period, subject to a floor of £2m in any one period. To the extent the cap has bitten in previous periods so as to result in a disallowance in that period, disallowed amounts may generally be carried forward and ‘reactivated’ in a subsequent period to the extent that the group (and the company to which the reactivation is allocated) has headroom in that period.

The carry forward rules are complex, particularly in relation to companies moving between groups, and are not considered in any detail in this article. Their inadequacy in dealing with volatility and business cycle points in a number of situations is currently under discussion with HMRC. For simplicity, we have assumed below that interest capacity for a period equals the interest allowance for that period.

Having established the identity of the UK corporation tax paying members of the worldwide group, it is necessary to calculate the ‘net tax-interest expense’ or ‘net-tax interest income’ of each of those companies. Those figures (positive and negative) must be aggregated to work out whether the worldwide group has ‘aggregate net tax-interest expense’ or ‘aggregate net tax-interest income’ for a period of account.

If the worldwide group has aggregate net-tax interest expense, it will be deductible only to the extent that it does not exceed 30% of the ‘aggregate tax-EBITDA’ of the UK corporation tax paying members of the worldwide group; or, if lower, the ‘adjusted net group-interest expense’ (ANGIE) of the worldwide group as a whole.

If the worldwide group has aggregate net tax-interest income, this will count towards the interest allowance for the current period of account. (This will increase the scope for the ‘reactivation’ of previously disallowed tax-interest expense amounts.)

Tax-interest expense amounts and tax-interest income amounts: These are the components of the net figures mentioned above and comprise:

Where the corporation tax on a tax-interest income amount is reduced by a credit for foreign tax, the tax-interest income amount is intended to be proportionately reduced.

Companies can elect for creditor loan relationships which are accounted for on a fair value basis to be treated as accounted for on an amortised cost basis, for the purposes of calculating tax-interest expense amounts and tax-interest income amounts. This provision was inserted primarily with insurers in mind, to prevent them ending up with (potentially disallowable) net tax-interest expense. The election is open to any sort of company, however.

Tax-EBITDA: The tax-EBITDA of a company means its profits or losses for corporation tax purposes, after excluding (i.e. adding back in the case of deductions/reliefs or deducting in the case of accretions):

Tax-EBITDA is further adjusted for certain amounts relating to long funding operating leases and short finance leases, in order to align the tax-EBITDA calculation with that of tax-interest amounts. Again for policy reasons, apportioned profits from a controlled foreign company (CFC) do not count towards tax-EBITDA. (However, the matched interest profits exemption in the CFC code is to be modified to prevent a CFC charge arising to the extent that apportioned qualifying loan relationship profits exceed aggregate net tax-interest expense.)

Each company’s tax-EBITDA (positive or negative) is aggregated to find the aggregate tax-EBITDA, which cannot be negative.

ANGIE: ANGIE – otherwise known as the modified debt cap (MDC), and purportedly designed to prevent groups gearing up to the 30% FR – is the sting in the tail in the case of the FR rule. ANGIE is the ‘net group-interest expense’ (NGIE) of the worldwide group. Very broadly speaking, it is the sum of those items in the consolidated profit and loss account which represent financing cost or financing income, as adjusted for certain items. (For example, financing costs which are capitalised, rather than being taken through profit and loss, are treated for ANGIE purposes as expensed in the period in which they are capitalised, rather than the period(s) in which they are expensed for accounting purposes as part of the write-down of the relevant asset.) The key point to note is that the modified debt cap looks to the net external expenses of the group, unlike the ‘available amount’ cap in the existing WWDC rules, which is a gross concept.

Take the example of an international conglomerate that operates across a variety of sectors. The sector in which it predominantly operates in the UK is one where businesses are typically highly leveraged, and the UK subgroup has raised external debt (comprising a mixture of bank and securitised debt) commensurate with that raised by UK headquartered groups operating in the same sector, with interest deductions of 45 on that debt amounting to approximately 45% of the group’s UK EBITDA. The UK operations have been further geared – to the extent thin capitalisation principles allow – with the issue of some shareholder debt to an offshore affiliate, thereby giving rise to a paradigm BEPS advantage. The other sectors in which the group operates internationally are traditionally more lowly leveraged and are funded locally with shareholder debt, reflecting the fact that the group has significant cash resources. Its financial services division in fact generates net interest income, with its net worldwide external expense in fact only amounting to 24.

With the introduction of the new UK interest barrier, our conglomerate fully expects to have to wave goodbye to any UK tax deductions on the shareholder debt (whi ch it considers a fair cop). How ever, interest on the bank debt and the notes issued by the securitisation vehicle – or at the very least, two thirds of that interest (30) – will remain deductible under the FR method, right? (Even that will put our conglomerate at a disadvantage to a similarly leveraged UK based competitor, which should in principle be able to deduct all of the 45 under the GR method (see below).) This ass umption is wrong: deductions will in fact be limited to 24 under the modified debt cap (compared with 45 under the current WWDC). This sort of result goes way beyond counteracting BEPS.

A group ratio election is not going to help the diversified group mentioned above to a better result, not least because the ANGIE restriction feeds into the concepts used for the purposes of the GR rule. However, in theory at least, it is designed to help groups which overall have external interest: EBITDA ratios which are higher than 30%. That said, it should not be assumed that the GR method will allow even a wholly UK group to deduct all of its external interest expense.

The basic GR rule

Under the GR, interest capacity will be limited to the lower of:

(i) the GR percentage of aggregate tax-EBITDA; and

(ii) ‘qualifying net group-interest expense’ (QNGIE) (the equivalent to the MDC in the GR context).

The GR percentage is calculated using the following formula (with the components taken from the group’s actual or notional IAS compliant financial statements):

The GR is deemed to be 100% where it would otherwise be negative or more than 100%, or where group-EBITDA is zero. This prevents very high GRs – a restriction that may feel unfair to businesses with long lead-in periods – and deals with scenarios where calculation would be impossible.

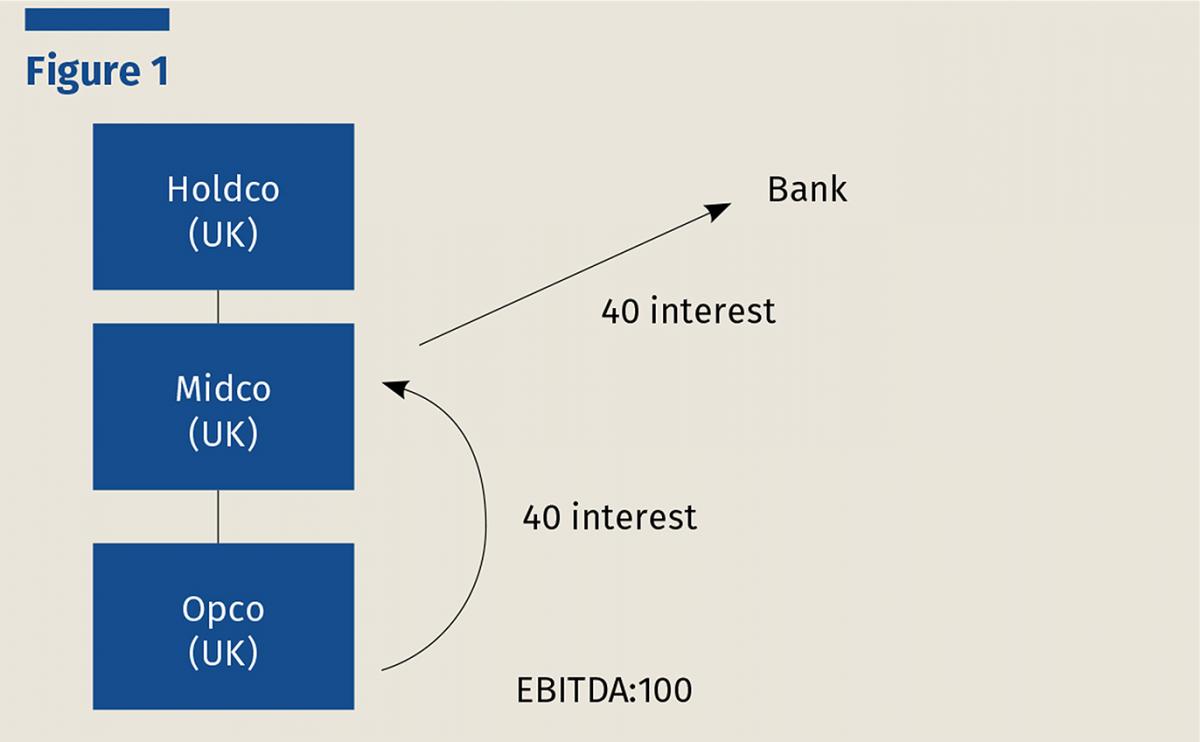

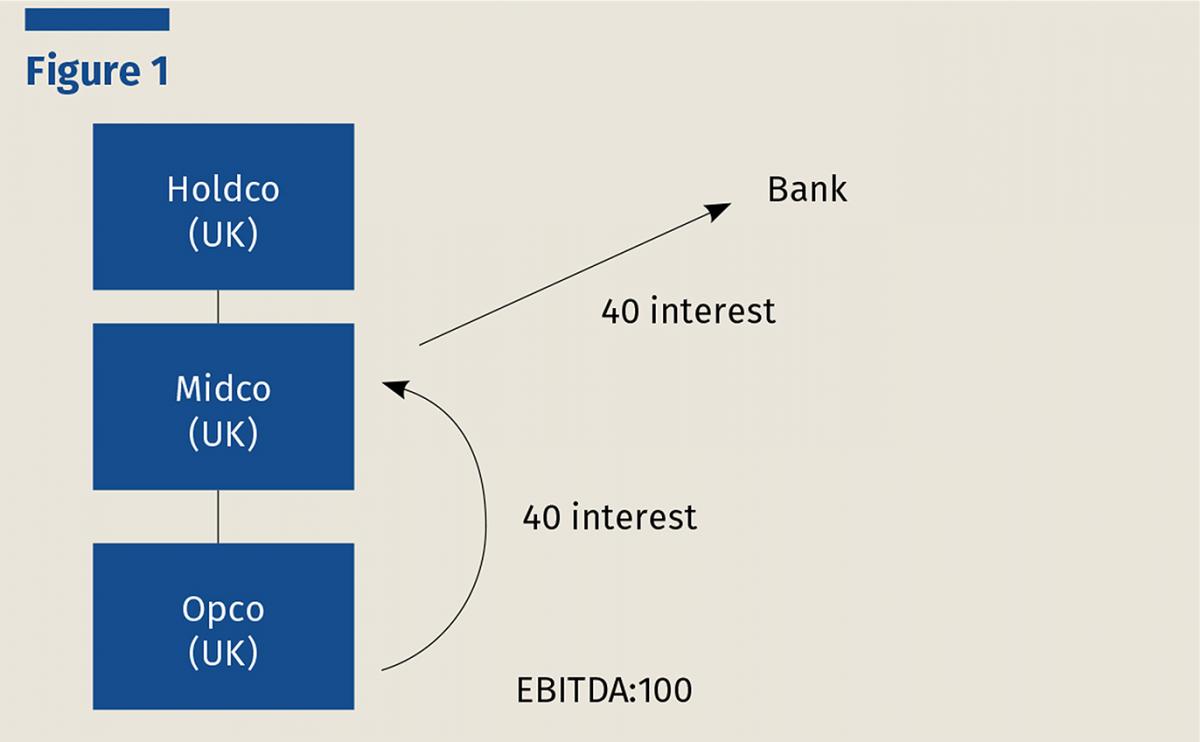

Figure 1 (below) shows a basic group structure where, before looking at the detail, one would expect the GR to improve the position. Under the FR, there would be a disallowance of 10 (30% of 100 being only 30). However, the GR should be 40% (40/100 x100), allowing full deductions for the 40 of net-interest (40% of 100).

QNGIE

QNGIE is calculated by taking ANGIE (see above) and making further downwards adjustments, the rationale for those adjustments being that interest on ‘equity-like’ debt should not improve deductibility in the UK. As currently drafted, however, those adjustments are likely to result in funding costs on many ordinary commercial borrowings from third parties (as the business community would typically understand those concepts) falling out of QNGIE. This would result in a GR rule so narrow in scope that one can only assume that its incorporation in the regime at all was a rather grudging one.

Debt owed to related parties: First, expenses on related party debt – that is to say, debt advanced by a lender which is a related party of any member of the group, including for example a special purpose issuer – must be deducted from QNGIE. This means that groups with shareholder or other related party debt will not be able to rely on that debt to increase deductions above 30%. The definition of related party is crucial and, unfortunately for the taxpayer, very wide. The government has wholeheartedly adopted the OECD’s recommendations, with some added UK twists.

Two persons will be related where:

i. they are consolidated;

ii. one person directly or indirectly participates in the other, or a third person so participates in each of them (similar to the transfer pricing test); or

iii. one of them has a 25% investment in the other, or a third person has a 25% investment in each of them.

It is this third limb that is the broadest. ‘Investment’ is measured in the alternative by reference to percentage entitlement to share capital or proceeds of the disposal thereof, voting power, entitlement to income distributions or entitlement to assets on a winding up, with only bank creditors excluded for the purposes of applying the last two tests. Moreover, not only do the normal wide rules around the attribution of others’ interests apply (including the interests of ‘connected persons’, which includes persons ‘acting together to secure or exercise control of a company’, under the existing definition in CTA 2010 s 1122), but in addition interests will also be aggregated where persons ‘act together so as to exert greater influence … or … so as to be able to achieve an outcome’ which could not be exerted or which would be more difficult to achieve on an individual basis. One way or another, it seems pretty clear that most consortium arrangements will be caught.

Some new special attribution provisions deem partners, or persons connected with them, to be connected with other partners or persons connected with them, even where the lending in question may have nothing to do with the partnership arrangements. This may also result in genuine third party debt not being respected as such for QNGIE purposes.

And that’s not all. Unsurprisingly, back-to-back lending through an unconnected lender will be caught. More alarmingly, however, a loan from an unconnected lender which is guaranteed by a related party will also be caught. Returning to the group in figure 1, if Holdco and/or Opco were to guarantee or otherwise provide security for the Midco debt (which would be the expected position under most bank facilities, particularly with respect to parent guarantees), the bank would be related and the GR would be 0%. It is hoped that this rather basic problem will be fixed in the next draft.

Some exceptions are included, but none seem wide enough (or easy enough to apply in practice) to provide any real comfort.

Equity notes: Expenses relating to equity notes are also deducted from QNGIE. ‘Equity notes’ has the same meaning as for the UK distributions code; broadly, debt which has an indefinite term or a term of more than 50 years (CTA 2010 s 1016). However, under the distributions code, interest payable on equity notes is only non-deductible if the equity notes are held by an associated or funded company (CTA 2010 s 1015(6)(b)). Rather surprisingly, and despite representations on this point, the government has not introduced similar secondary criteria for the purpose of calculating QNGIE. Returning to figure 1, if Midco had issued perpetual debt to the bank, interest on that debt may be deductible under the UK domestic rules (given that the bank is neither an associated nor funded company); nevertheless, this would not count towards QNGIE (again reducing the GR to 0%).

Results-dependent securities: Finally, expenses relating to results-dependent securities are deducted from QNGIE. A new, wider definition of results dependence is used, rather than there being a cross reference to the UK distributions code. Debt will be results dependent if interest depends on either the results of the issuer’s business or (and this is the new part) the results of any other group member’s business. What is more, whereas distribution treatment for results-dependent debt is switched off where the lender is within the UK corporation tax charge (so that interest remains deductible for the borrower), results-dependent debt which is or would be deductible will still not count as QNGIE. It is understood that HMRC is holding its line on this, although it has apparently conceded that reverse ratchets – i.e. where interest increases as results deteriorate, or vice versa – should not be regarded as results dependent for QNGIE purposes. This is expected to be reflected in the next version of the rules. A rule providing that interest on results-dependent debt issued by securitisation companies will also not be excluded from QNGIE is expected to be contained in regulations.

Double taxation: The above brings points around double taxation into stark focus. The bank in figure 1 may well suffer tax (perhaps even UK corporation tax) or withholding tax (if it is in a tax haven) on the interest. However, there is nothing in the rules (in contrast to, say, the transfer pricing rules or the UK distributions code) to switch off that tax if the interest is non-deductible.

Non-UK headed groups: The UK market has developed in a way that avoids features that would inadvertently trigger non-deductibility, but that will not be the case elsewhere. Non-UK headed groups, which have issued debt to fund UK sub-groups, may well be tripped up. Indeed, if such a group decides to raise new debt, and carefully avoids problematic features that it would normally include in its debt, will that trigger the new TAAR that has been included in the new rules?

Group-EBITDA is: PBT (the group’s profit before tax shown in its consolidated P&L) + I (NGIE, i.e. adding back interest, but before any of the adjustments that were made to calculate ANGIE and QNGIE) + DA (the depreciation and amortisation adjustment).

The DA adjustment involves:

There are no adjustments to group-EBITDA for gains that benefit from the UK substantial shareholder exemption or dividend exemption – a conscious policy decision. To demonstrate this using the example in figure 1, imagine if Opco invested its spare cash in shares, and received 15 of dividend income. That dividend income would not be included in the UK group’s aggregate tax-EBITDA, but it would be included in group-EBITDA. The GR would therefore reduce to 34.8% (40/115), and some interest deductions would be denied. The government would no doubt say this is appropriate: the debt of the group is ‘used’ not only to generate taxable profits but also non-taxable income, and so only a proportion of the interest should be deductible.

Note that group-EBITDA (as well as NGIE, ANGIE and QNGIE) is calculated on the assumption that the Loan Relationship and Derivative Contracts (Disregard and Bringing into Account of Profits and Losses) Regulations, SI 2004/3256, apply for the purpose of determining certain accounting entries, where derivatives are performing a hedging function at a group level. The effect will broadly be to substitute notional accruals accounting-based entries for fair value movements.

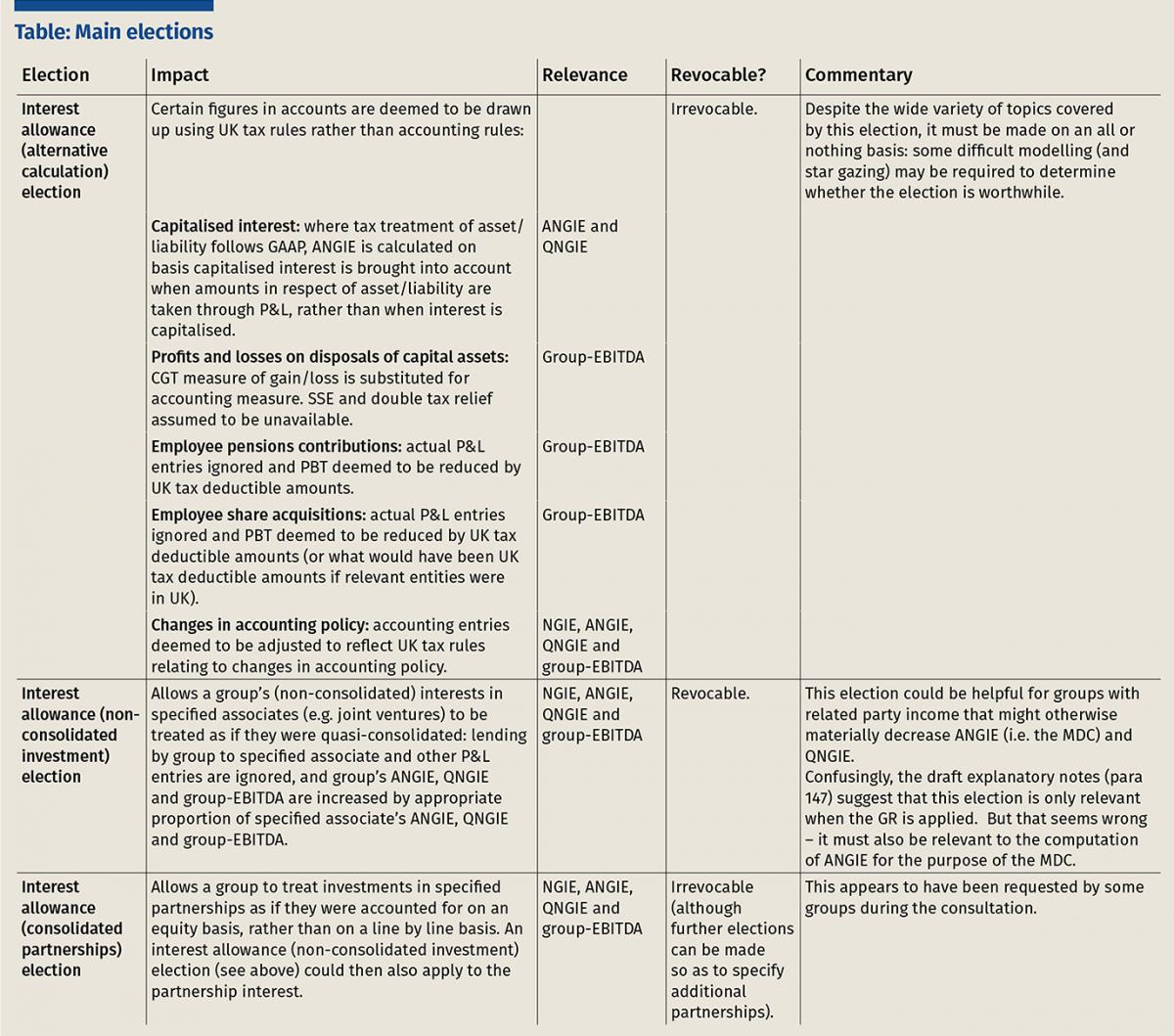

Elections

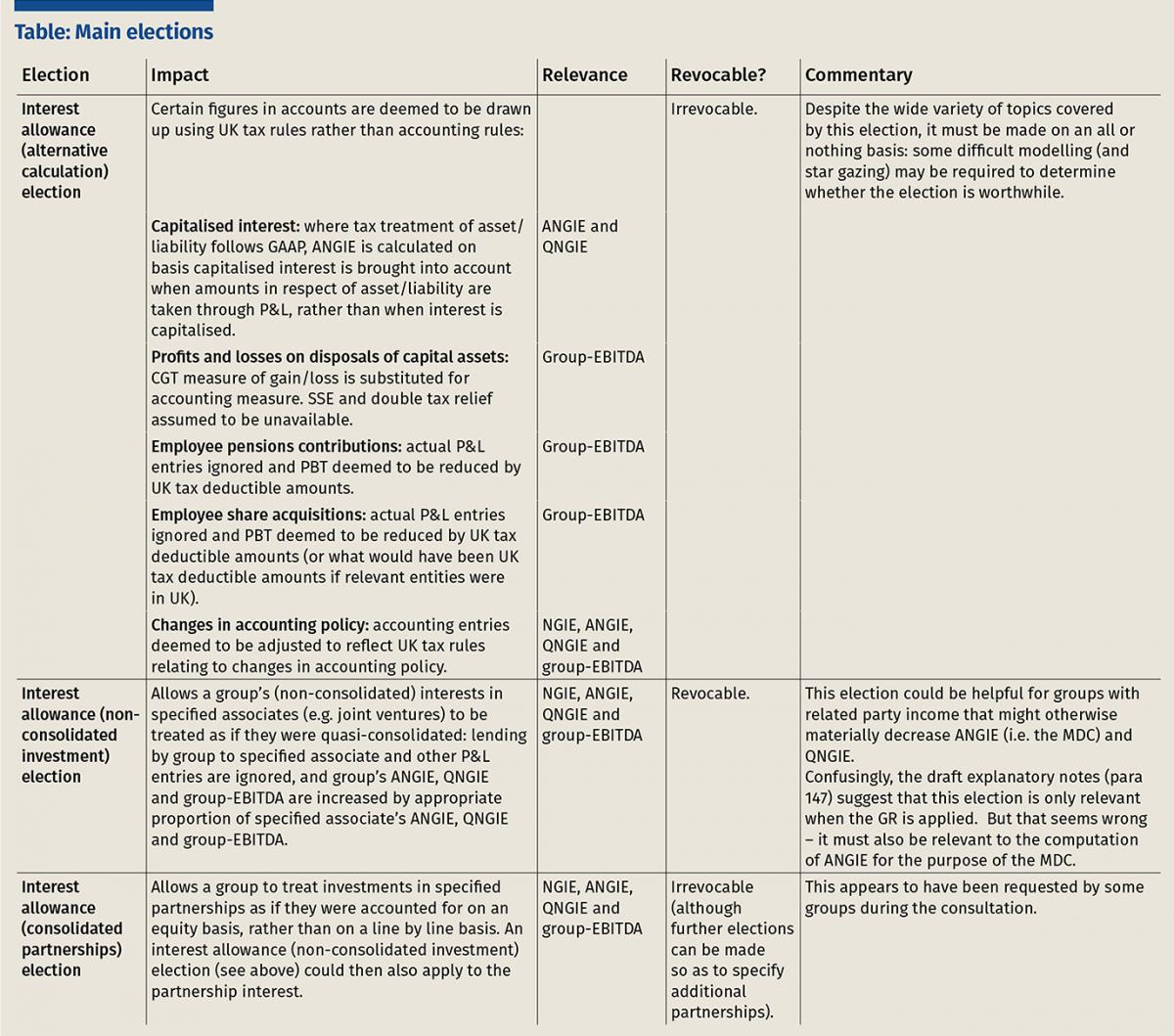

A number of elections, the main ones being summarised in the table below, can be made so as to alter the computation of NGIE, ANGIE, QNGIE and/or group-EBITDA.

International conglomerates

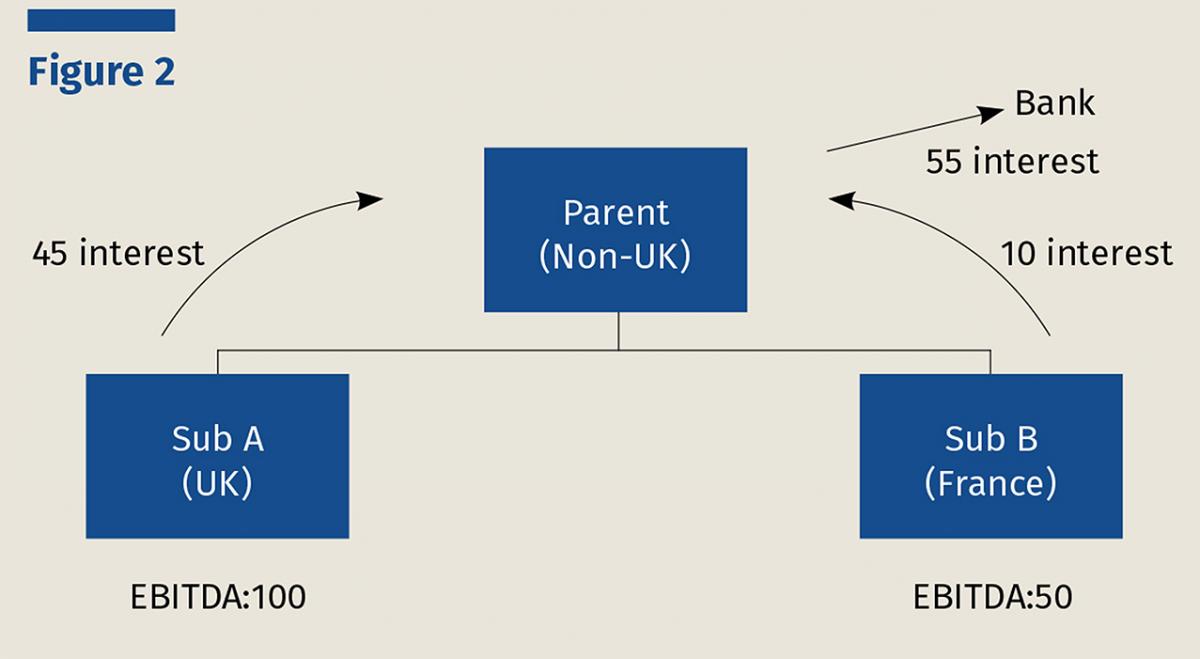

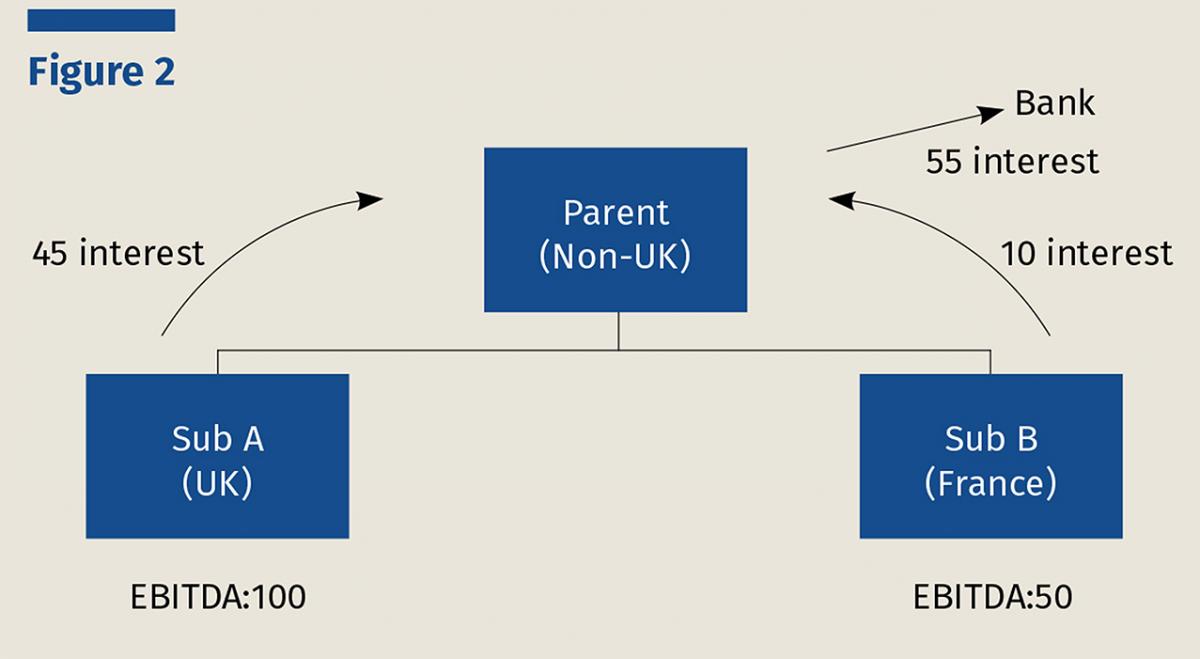

Even those international conglomerates which can (perhaps against the odds) take advantage of the GR method may find that it nevertheless leads to surprising and unpredictable results. Take the group in figure 2 (below): a parent company with two operating subsidiaries, to which it on-lends external finance. Sub A is operating in a highly leveraged UK sector and Sub B in a different sector in France. Sub A needs to rely on the GR to obtain full deductions for its debt. However, the GR will be depressed because of its less-leveraged sister subsidiary (36.7%, rather than the 45% it might expect if it were standalone). Indeed, if profitability in Sub B were to increase, but Sub A’s profitability remained the same, the GR would decrease further.

The government might say that these results are appropriate – the international group is choosing to debt finance its activities in the UK, despite relying on equity finance elsewhere. However, it remains the case that this group will be at a disadvantage when compared to those that are only active in the UK sector.

As indicated in the table above, a group can elect to treat a non-consolidated joint venture (JV) as quasi-consolidated for the purposes of applying the new rules with respect to that group. What about the position of the JV group itself?

Here, the rules again risk some arbitrary outcomes. Tax relief for the JV will depend on whether the JV is actually consolidated with any investor or not (a status which could turn on a mere 1% shift in percentage ownership); and, if not, whether it is funded by external or shareholder debt. (This presupposes that the JV is tax opaque. Tax deductions, if any, would be taken at the level of the investor in the case of a transparent JV.)

Given the definition of ‘worldwide group’ (see above), a consolidated JV forms part of the consolidating investor’s group for the purposes of the rules. Tax relief in the JV (which will affect returns for all investors) is a function of the consolidating investor’s tax profile, including its group ratio. This ‘top-down’ approach to interest relief is clearly inappropriate in many cases.

Contrast a non-consolidated JV, which forms its own group for these purposes. The ‘top-down’ approach is avoided, but the application of the rules now depends on how the JV is funded. External debt of the JV counts towards the JV’s group ratio; in contrast (given the breadth of the ‘related party’ definition) shareholder debt, most likely, does not – including where it represents external debt raised at investor level. For a JV operating in a highly leveraged industry, where for ‘good’ non-tax commercial reasons, debt may well be preferred, this distinction could (without more) be critical.

A group ratio (blended) election is designed to alleviate some of these problems. It allows an (unconsolidated) JV to calculate its group ratio by reference to a blended ratio, calculated (broadly speaking) by applying each ‘investor’s applicable ratio’ (the higher of: (i) 30%; (ii) the JV group ratio; and (iii) the investor group’s group ratio) to its proportionate share in the JV, and aggregating the results. While this introduces a ‘top-down’ approach for unconsolidated JVs, it does so in a more proportionate way than for consolidated JVs. Nevertheless, it does not entirely align the treatment of consolidated and unconsolidated JVs, nor the treatment of an unconsolidated JV with external debt with that of a JV with shareholder debt, but it should bring them closer.

That said, the election as drafted appears to be flawed. It substitutes the blended ratio for what would otherwise be the JV group’s ratio for the purposes of applying the GR rule, but it does not switch off the ‘lower of’ aspect of the GR rule, pursuant to which the interest allowance is calculated, as the lower of the group ratio as applied to aggregate tax-EBITDA and QNGIE. Accordingly, a JV funded with shareholder (related party) debt – whose QNGIE would be 0 – would not be able to access its investors’ ratios, thereby defeating the purpose of having the election facility in the first place. It is hoped that this will also be fixed in the next version of the legislation.

The legislation contains a public benefit infrastructure exemption (PBIE). This follows intensive lobbying from infrastructure groups which have cited the UK’s high proportion of critical infrastructure in private ownership and the fact that infrastructure assets can support high levels of gearing.

Headline points are that the proposed PBIE (unlike the public benefit project exemption (PBPE) proposed by the OECD) operates on a company-by-company rather than a project-by-project basis. A qualifying infrastructure company can make an election for its tax-EBITDA and exempt amounts to be effectively excluded from the group’s interest restriction calculations.

The scope of infrastructure activities qualifying for the PBIE is quite a bit wider than originally proposed (and wider than under the PBPE). It includes the usual categories of utilities; telecommunications; transport; health and education; court and prisons; and training facilities. Perhaps surprisingly, it also includes buildings (or parts of buildings) let on a short-term basis, as explained further below.

However, qualifying infrastructure companies entitled to elect for the PBIE are narrowly defined. They must be UK corporation taxpayers with no or only insignificant non-qualifying activities (this includes not owning shares in or loans to non-qualifying companies). In a group situation, this means that a subsidiary’s activities can taint those of its parent and prevent the parent from qualifying for the PBIE. And a company will not qualify if it has been loaded up with debt relative to other comparable group entities.

The exempted amounts are also narrowly defined. Subject to a limited grandfathering rule, the exemption will only apply to interest on third party, non-recourse loans and not to related party debt or loans guaranteed by related parties.

These points, together with the inflexibility of an election that can only be revoked (or refreshed, once revoked) after five years, mean the PBIE, as currently conceived, is of quite limited application for more complex infrastructure groups. These will need to fall back on the group ratio or the 30% fixed ratio (watching out for the nasty points mentioned above). Even where the conditions are met, given the long term nature of infrastructure projects and the very real prospect of changes in ownership, it may be difficult for groups to be confident that a PBIE election will always be in the best interests of the group.

There are some specific rules for the real estate sector, including an extension to the PBIE and rules on REITs.

The PBIE does away with the requirement for a ‘public infrastructure asset’ to meet the public benefit test, in circumstances where the asset is a building that forms part of a UK property business and is, or is to be, let on a short-term basis to an unrelated party (‘short-term’ broadly means 50 years or less). This is expected to help commercial property groups; however, given the other PBIE requirements, care must be taken that the property is in vehicles that neither carry on significant other activities nor have subsidiaries outside the UK corporation tax net.

It remains unclear whether the PBIE caters for development-phase properties. The ‘provision’ of public infrastructure assets helpfully includes ‘acquisition, design, construction, conversion, improvement, operation or repair’, although this will only assist where the taxpayer can show that the building is ‘to be let’ to an unrelated party. Grandfathering of old loans is unlikely to benefit, since when the loan was entered into it must have been possible to predict future infrastructure receipts by reference to contracts with (or tendered by) public bodies; this is not expected to apply in most commercial property scenarios.

The property industry raised a concern earlier in the consultation process that the rules could force a REIT, which is obliged to distribute at least 90% of its profits from its exempt property rental business (as they would be calculated for corporation tax purposes) as a property income distribution (PID), to pay excessive PIDs. Broadly speaking, this has been fixed in the latest draft of the legislation by limiting any disallowance to the exempt side of a REIT’s business.

The government has sought to justify its decision not to exempt banking and insurance groups from the scope of the new rules, on the basis that the nature of their businesses is such that they would be expected to be in an overall net interest income position and accordingly they should not be faced with restrictions under the new rules. This has proved to be an over-simplistic assumption, particularly for non-UK headquartered banks and insurers and those groups that carry on a fairly diverse range of businesses within the financial sector. Representative bodies are understood to be in discussion with HMRC in relation to some of the problems.

Ring fenced oil and gas businesses, which are already subject to quite strict limitations on interest deductibility, are exempt from the new rules. Activities outside the ring fence will be subject to the rules in the normal way.

The problems so far identified with the new rules may prove to be the tip of the iceberg. It will be important for HMRC to stay in listening mode, as the regime beds down over the next or year or so, and be prepared to adjust it where necessary, especially given the haste with which such a complex bit of legislation is being ushered in.

The authors thank colleagues Helen Buchanan, Faye Coates and Sam Withnall for their contribution to this article.

The UK is pushing ahead with an interest barrier, following BEPS Action 4. In addition to a fixed ratio rule and a group ratio rule, the effect of which will be to restrict UK tax deductions to a percentage of UK taxable EBITDA, the new regime includes a modified debt cap, which will further restrict deductions to the extent that they exceed the group’s net external interest costs. The rules may well affect groups that have never used BEPS strategies. The scope of what counts as qualifying debt for group ratio purposes is so narrow that even wholly UK based groups could find themselves unable to deduct all of their external interest expense.

Despite having previously resisted a ‘structural restriction’ for interest deductions – it was expressly rejected as part of the package of reforms for the taxation of foreign profits implemented a few years ago – the UK government has been quick to implement the OECD’s recommendations on BEPS Action 4 (limiting base erosion involving interest deductions and other financial payments). The basic ingredients of the new interest barrier, effective from 1 April 2017, have been well publicised: ther e is to be a fixed ratio (FR) rule, under which a group will be able to deduct net UK interest costs only to the extent that they do not exceed 30% of UK taxable EBITDA; and this is supplemented by an elective group ratio (GR) rule, pursuant to which an overall more highly leveraged group can substitute the 30% with a percentage derived from taking its group-wide third party interest expense over group-wide EBITDA.

So far, so simple, although the devil is of course in the detail. The new UK rules include some nasty tweaks to the OECD recommendations, which mean they may well restrict deductions for groups whose financing arrangements do not involve BEPS (or indeed any cross-border element). Some of the more flagrant examples of overreaching are touched on below in the course of outlining the new rules. While HMRC has already indicated that it is not likely to change its mind on certain aspects, some obvious glitches are expected to be fixed in the next version of the draft legislation. (An incomplete version was issued in December, with a full version published at the end of January for further consultation.)

The new rules will form a new Part 10 of and a new Sch 7A to TIOPA 2010. Schedule 7A will contain the administrative rules dealing with, among other things, the preparation and submission of interest restriction returns and the allocation of amounts amongst group members. Although not covered in this article, familiarity with these rules will be important in practice, including in an M&A context where companies are leaving and joining groups.

In order to operate the new rules (whether under the FR or GR method), it is necessary to identify the ‘worldwide group’ and its members, and the ‘period of account’ of that worldwide group. A worldwide group (group having the meaning given by the international accounting standards (IAS)) is constituted by the ‘ultimate parent’ and its ‘consolidated subsidiaries’. Some of these terms will be familiar from the existing worldwide debt cap (WWDC) regime, but they are in fact (subtly) different concepts.

Ultimate parent: An ultimate parent is a member of an IAS group, which is not a consolidated subsidiary of any other entity and which is:

i. a body corporate (not being a limited liability partnership or foreign entity which would be regarded as a partnership applying UK principles);

ii. an entity where the entitlement of investors to the entity’s profits is dependent on a decision taken by the entity; or

iii. an entity the shares or interests in which are listed and held by participators, none of which holds more than 10% by value.

(Determining whether condition (ii), in particular, is met is already expected to cause difficulties in practice.)

Consolidated subsidiary: A consolidated subsidiary is a subsidiary in the IAS sense which is not fair valued through profit or loss; in other words, a subsidiary which is consolidated on a line by line basis.

Period of account: This will essentially be the period in respect of which consolidated financial statements are drawn up. The interest barrier regime will operate by reference to actual or notional IAS compliant financial statements.

The companies whose financing costs are vulnerable to restriction under the new rules, and whose taxable EBITDA counts for the purposes of applying the FR and GR rules, are the UK corporation tax paying members of the worldwide group (whether UK resident or with UK permanent establishments). Very broadly – although the legislative approach to this is rather cumbersome – a company’s accounting period for corporation tax purposes will correspond to the worldwide group’s period of account to the extent the periods overlap.

‘Interest allowance’ is calculated for a period of account of a worldwide group applying the FR method; or, where a group ratio election is in place in respect of that period, the GR method. That interest allowance, taken together with any unused interest allowances from the previous five years, then represents the ‘interest capacity’ of the worldwide group for the period. This is the cap on UK tax deductions for financing costs for that period, subject to a floor of £2m in any one period. To the extent the cap has bitten in previous periods so as to result in a disallowance in that period, disallowed amounts may generally be carried forward and ‘reactivated’ in a subsequent period to the extent that the group (and the company to which the reactivation is allocated) has headroom in that period.

The carry forward rules are complex, particularly in relation to companies moving between groups, and are not considered in any detail in this article. Their inadequacy in dealing with volatility and business cycle points in a number of situations is currently under discussion with HMRC. For simplicity, we have assumed below that interest capacity for a period equals the interest allowance for that period.

Having established the identity of the UK corporation tax paying members of the worldwide group, it is necessary to calculate the ‘net tax-interest expense’ or ‘net-tax interest income’ of each of those companies. Those figures (positive and negative) must be aggregated to work out whether the worldwide group has ‘aggregate net tax-interest expense’ or ‘aggregate net tax-interest income’ for a period of account.

If the worldwide group has aggregate net-tax interest expense, it will be deductible only to the extent that it does not exceed 30% of the ‘aggregate tax-EBITDA’ of the UK corporation tax paying members of the worldwide group; or, if lower, the ‘adjusted net group-interest expense’ (ANGIE) of the worldwide group as a whole.

If the worldwide group has aggregate net tax-interest income, this will count towards the interest allowance for the current period of account. (This will increase the scope for the ‘reactivation’ of previously disallowed tax-interest expense amounts.)

Tax-interest expense amounts and tax-interest income amounts: These are the components of the net figures mentioned above and comprise:

Where the corporation tax on a tax-interest income amount is reduced by a credit for foreign tax, the tax-interest income amount is intended to be proportionately reduced.

Companies can elect for creditor loan relationships which are accounted for on a fair value basis to be treated as accounted for on an amortised cost basis, for the purposes of calculating tax-interest expense amounts and tax-interest income amounts. This provision was inserted primarily with insurers in mind, to prevent them ending up with (potentially disallowable) net tax-interest expense. The election is open to any sort of company, however.

Tax-EBITDA: The tax-EBITDA of a company means its profits or losses for corporation tax purposes, after excluding (i.e. adding back in the case of deductions/reliefs or deducting in the case of accretions):

Tax-EBITDA is further adjusted for certain amounts relating to long funding operating leases and short finance leases, in order to align the tax-EBITDA calculation with that of tax-interest amounts. Again for policy reasons, apportioned profits from a controlled foreign company (CFC) do not count towards tax-EBITDA. (However, the matched interest profits exemption in the CFC code is to be modified to prevent a CFC charge arising to the extent that apportioned qualifying loan relationship profits exceed aggregate net tax-interest expense.)

Each company’s tax-EBITDA (positive or negative) is aggregated to find the aggregate tax-EBITDA, which cannot be negative.

ANGIE: ANGIE – otherwise known as the modified debt cap (MDC), and purportedly designed to prevent groups gearing up to the 30% FR – is the sting in the tail in the case of the FR rule. ANGIE is the ‘net group-interest expense’ (NGIE) of the worldwide group. Very broadly speaking, it is the sum of those items in the consolidated profit and loss account which represent financing cost or financing income, as adjusted for certain items. (For example, financing costs which are capitalised, rather than being taken through profit and loss, are treated for ANGIE purposes as expensed in the period in which they are capitalised, rather than the period(s) in which they are expensed for accounting purposes as part of the write-down of the relevant asset.) The key point to note is that the modified debt cap looks to the net external expenses of the group, unlike the ‘available amount’ cap in the existing WWDC rules, which is a gross concept.

Take the example of an international conglomerate that operates across a variety of sectors. The sector in which it predominantly operates in the UK is one where businesses are typically highly leveraged, and the UK subgroup has raised external debt (comprising a mixture of bank and securitised debt) commensurate with that raised by UK headquartered groups operating in the same sector, with interest deductions of 45 on that debt amounting to approximately 45% of the group’s UK EBITDA. The UK operations have been further geared – to the extent thin capitalisation principles allow – with the issue of some shareholder debt to an offshore affiliate, thereby giving rise to a paradigm BEPS advantage. The other sectors in which the group operates internationally are traditionally more lowly leveraged and are funded locally with shareholder debt, reflecting the fact that the group has significant cash resources. Its financial services division in fact generates net interest income, with its net worldwide external expense in fact only amounting to 24.

With the introduction of the new UK interest barrier, our conglomerate fully expects to have to wave goodbye to any UK tax deductions on the shareholder debt (whi ch it considers a fair cop). How ever, interest on the bank debt and the notes issued by the securitisation vehicle – or at the very least, two thirds of that interest (30) – will remain deductible under the FR method, right? (Even that will put our conglomerate at a disadvantage to a similarly leveraged UK based competitor, which should in principle be able to deduct all of the 45 under the GR method (see below).) This ass umption is wrong: deductions will in fact be limited to 24 under the modified debt cap (compared with 45 under the current WWDC). This sort of result goes way beyond counteracting BEPS.

A group ratio election is not going to help the diversified group mentioned above to a better result, not least because the ANGIE restriction feeds into the concepts used for the purposes of the GR rule. However, in theory at least, it is designed to help groups which overall have external interest: EBITDA ratios which are higher than 30%. That said, it should not be assumed that the GR method will allow even a wholly UK group to deduct all of its external interest expense.

The basic GR rule

Under the GR, interest capacity will be limited to the lower of:

(i) the GR percentage of aggregate tax-EBITDA; and

(ii) ‘qualifying net group-interest expense’ (QNGIE) (the equivalent to the MDC in the GR context).

The GR percentage is calculated using the following formula (with the components taken from the group’s actual or notional IAS compliant financial statements):

The GR is deemed to be 100% where it would otherwise be negative or more than 100%, or where group-EBITDA is zero. This prevents very high GRs – a restriction that may feel unfair to businesses with long lead-in periods – and deals with scenarios where calculation would be impossible.

Figure 1 (below) shows a basic group structure where, before looking at the detail, one would expect the GR to improve the position. Under the FR, there would be a disallowance of 10 (30% of 100 being only 30). However, the GR should be 40% (40/100 x100), allowing full deductions for the 40 of net-interest (40% of 100).

QNGIE

QNGIE is calculated by taking ANGIE (see above) and making further downwards adjustments, the rationale for those adjustments being that interest on ‘equity-like’ debt should not improve deductibility in the UK. As currently drafted, however, those adjustments are likely to result in funding costs on many ordinary commercial borrowings from third parties (as the business community would typically understand those concepts) falling out of QNGIE. This would result in a GR rule so narrow in scope that one can only assume that its incorporation in the regime at all was a rather grudging one.

Debt owed to related parties: First, expenses on related party debt – that is to say, debt advanced by a lender which is a related party of any member of the group, including for example a special purpose issuer – must be deducted from QNGIE. This means that groups with shareholder or other related party debt will not be able to rely on that debt to increase deductions above 30%. The definition of related party is crucial and, unfortunately for the taxpayer, very wide. The government has wholeheartedly adopted the OECD’s recommendations, with some added UK twists.

Two persons will be related where:

i. they are consolidated;

ii. one person directly or indirectly participates in the other, or a third person so participates in each of them (similar to the transfer pricing test); or

iii. one of them has a 25% investment in the other, or a third person has a 25% investment in each of them.

It is this third limb that is the broadest. ‘Investment’ is measured in the alternative by reference to percentage entitlement to share capital or proceeds of the disposal thereof, voting power, entitlement to income distributions or entitlement to assets on a winding up, with only bank creditors excluded for the purposes of applying the last two tests. Moreover, not only do the normal wide rules around the attribution of others’ interests apply (including the interests of ‘connected persons’, which includes persons ‘acting together to secure or exercise control of a company’, under the existing definition in CTA 2010 s 1122), but in addition interests will also be aggregated where persons ‘act together so as to exert greater influence … or … so as to be able to achieve an outcome’ which could not be exerted or which would be more difficult to achieve on an individual basis. One way or another, it seems pretty clear that most consortium arrangements will be caught.

Some new special attribution provisions deem partners, or persons connected with them, to be connected with other partners or persons connected with them, even where the lending in question may have nothing to do with the partnership arrangements. This may also result in genuine third party debt not being respected as such for QNGIE purposes.

And that’s not all. Unsurprisingly, back-to-back lending through an unconnected lender will be caught. More alarmingly, however, a loan from an unconnected lender which is guaranteed by a related party will also be caught. Returning to the group in figure 1, if Holdco and/or Opco were to guarantee or otherwise provide security for the Midco debt (which would be the expected position under most bank facilities, particularly with respect to parent guarantees), the bank would be related and the GR would be 0%. It is hoped that this rather basic problem will be fixed in the next draft.

Some exceptions are included, but none seem wide enough (or easy enough to apply in practice) to provide any real comfort.

Equity notes: Expenses relating to equity notes are also deducted from QNGIE. ‘Equity notes’ has the same meaning as for the UK distributions code; broadly, debt which has an indefinite term or a term of more than 50 years (CTA 2010 s 1016). However, under the distributions code, interest payable on equity notes is only non-deductible if the equity notes are held by an associated or funded company (CTA 2010 s 1015(6)(b)). Rather surprisingly, and despite representations on this point, the government has not introduced similar secondary criteria for the purpose of calculating QNGIE. Returning to figure 1, if Midco had issued perpetual debt to the bank, interest on that debt may be deductible under the UK domestic rules (given that the bank is neither an associated nor funded company); nevertheless, this would not count towards QNGIE (again reducing the GR to 0%).

Results-dependent securities: Finally, expenses relating to results-dependent securities are deducted from QNGIE. A new, wider definition of results dependence is used, rather than there being a cross reference to the UK distributions code. Debt will be results dependent if interest depends on either the results of the issuer’s business or (and this is the new part) the results of any other group member’s business. What is more, whereas distribution treatment for results-dependent debt is switched off where the lender is within the UK corporation tax charge (so that interest remains deductible for the borrower), results-dependent debt which is or would be deductible will still not count as QNGIE. It is understood that HMRC is holding its line on this, although it has apparently conceded that reverse ratchets – i.e. where interest increases as results deteriorate, or vice versa – should not be regarded as results dependent for QNGIE purposes. This is expected to be reflected in the next version of the rules. A rule providing that interest on results-dependent debt issued by securitisation companies will also not be excluded from QNGIE is expected to be contained in regulations.

Double taxation: The above brings points around double taxation into stark focus. The bank in figure 1 may well suffer tax (perhaps even UK corporation tax) or withholding tax (if it is in a tax haven) on the interest. However, there is nothing in the rules (in contrast to, say, the transfer pricing rules or the UK distributions code) to switch off that tax if the interest is non-deductible.

Non-UK headed groups: The UK market has developed in a way that avoids features that would inadvertently trigger non-deductibility, but that will not be the case elsewhere. Non-UK headed groups, which have issued debt to fund UK sub-groups, may well be tripped up. Indeed, if such a group decides to raise new debt, and carefully avoids problematic features that it would normally include in its debt, will that trigger the new TAAR that has been included in the new rules?

Group-EBITDA is: PBT (the group’s profit before tax shown in its consolidated P&L) + I (NGIE, i.e. adding back interest, but before any of the adjustments that were made to calculate ANGIE and QNGIE) + DA (the depreciation and amortisation adjustment).

The DA adjustment involves:

There are no adjustments to group-EBITDA for gains that benefit from the UK substantial shareholder exemption or dividend exemption – a conscious policy decision. To demonstrate this using the example in figure 1, imagine if Opco invested its spare cash in shares, and received 15 of dividend income. That dividend income would not be included in the UK group’s aggregate tax-EBITDA, but it would be included in group-EBITDA. The GR would therefore reduce to 34.8% (40/115), and some interest deductions would be denied. The government would no doubt say this is appropriate: the debt of the group is ‘used’ not only to generate taxable profits but also non-taxable income, and so only a proportion of the interest should be deductible.

Note that group-EBITDA (as well as NGIE, ANGIE and QNGIE) is calculated on the assumption that the Loan Relationship and Derivative Contracts (Disregard and Bringing into Account of Profits and Losses) Regulations, SI 2004/3256, apply for the purpose of determining certain accounting entries, where derivatives are performing a hedging function at a group level. The effect will broadly be to substitute notional accruals accounting-based entries for fair value movements.

Elections

A number of elections, the main ones being summarised in the table below, can be made so as to alter the computation of NGIE, ANGIE, QNGIE and/or group-EBITDA.

International conglomerates

Even those international conglomerates which can (perhaps against the odds) take advantage of the GR method may find that it nevertheless leads to surprising and unpredictable results. Take the group in figure 2 (below): a parent company with two operating subsidiaries, to which it on-lends external finance. Sub A is operating in a highly leveraged UK sector and Sub B in a different sector in France. Sub A needs to rely on the GR to obtain full deductions for its debt. However, the GR will be depressed because of its less-leveraged sister subsidiary (36.7%, rather than the 45% it might expect if it were standalone). Indeed, if profitability in Sub B were to increase, but Sub A’s profitability remained the same, the GR would decrease further.

The government might say that these results are appropriate – the international group is choosing to debt finance its activities in the UK, despite relying on equity finance elsewhere. However, it remains the case that this group will be at a disadvantage when compared to those that are only active in the UK sector.

As indicated in the table above, a group can elect to treat a non-consolidated joint venture (JV) as quasi-consolidated for the purposes of applying the new rules with respect to that group. What about the position of the JV group itself?

Here, the rules again risk some arbitrary outcomes. Tax relief for the JV will depend on whether the JV is actually consolidated with any investor or not (a status which could turn on a mere 1% shift in percentage ownership); and, if not, whether it is funded by external or shareholder debt. (This presupposes that the JV is tax opaque. Tax deductions, if any, would be taken at the level of the investor in the case of a transparent JV.)

Given the definition of ‘worldwide group’ (see above), a consolidated JV forms part of the consolidating investor’s group for the purposes of the rules. Tax relief in the JV (which will affect returns for all investors) is a function of the consolidating investor’s tax profile, including its group ratio. This ‘top-down’ approach to interest relief is clearly inappropriate in many cases.

Contrast a non-consolidated JV, which forms its own group for these purposes. The ‘top-down’ approach is avoided, but the application of the rules now depends on how the JV is funded. External debt of the JV counts towards the JV’s group ratio; in contrast (given the breadth of the ‘related party’ definition) shareholder debt, most likely, does not – including where it represents external debt raised at investor level. For a JV operating in a highly leveraged industry, where for ‘good’ non-tax commercial reasons, debt may well be preferred, this distinction could (without more) be critical.

A group ratio (blended) election is designed to alleviate some of these problems. It allows an (unconsolidated) JV to calculate its group ratio by reference to a blended ratio, calculated (broadly speaking) by applying each ‘investor’s applicable ratio’ (the higher of: (i) 30%; (ii) the JV group ratio; and (iii) the investor group’s group ratio) to its proportionate share in the JV, and aggregating the results. While this introduces a ‘top-down’ approach for unconsolidated JVs, it does so in a more proportionate way than for consolidated JVs. Nevertheless, it does not entirely align the treatment of consolidated and unconsolidated JVs, nor the treatment of an unconsolidated JV with external debt with that of a JV with shareholder debt, but it should bring them closer.

That said, the election as drafted appears to be flawed. It substitutes the blended ratio for what would otherwise be the JV group’s ratio for the purposes of applying the GR rule, but it does not switch off the ‘lower of’ aspect of the GR rule, pursuant to which the interest allowance is calculated, as the lower of the group ratio as applied to aggregate tax-EBITDA and QNGIE. Accordingly, a JV funded with shareholder (related party) debt – whose QNGIE would be 0 – would not be able to access its investors’ ratios, thereby defeating the purpose of having the election facility in the first place. It is hoped that this will also be fixed in the next version of the legislation.

The legislation contains a public benefit infrastructure exemption (PBIE). This follows intensive lobbying from infrastructure groups which have cited the UK’s high proportion of critical infrastructure in private ownership and the fact that infrastructure assets can support high levels of gearing.

Headline points are that the proposed PBIE (unlike the public benefit project exemption (PBPE) proposed by the OECD) operates on a company-by-company rather than a project-by-project basis. A qualifying infrastructure company can make an election for its tax-EBITDA and exempt amounts to be effectively excluded from the group’s interest restriction calculations.

The scope of infrastructure activities qualifying for the PBIE is quite a bit wider than originally proposed (and wider than under the PBPE). It includes the usual categories of utilities; telecommunications; transport; health and education; court and prisons; and training facilities. Perhaps surprisingly, it also includes buildings (or parts of buildings) let on a short-term basis, as explained further below.

However, qualifying infrastructure companies entitled to elect for the PBIE are narrowly defined. They must be UK corporation taxpayers with no or only insignificant non-qualifying activities (this includes not owning shares in or loans to non-qualifying companies). In a group situation, this means that a subsidiary’s activities can taint those of its parent and prevent the parent from qualifying for the PBIE. And a company will not qualify if it has been loaded up with debt relative to other comparable group entities.

The exempted amounts are also narrowly defined. Subject to a limited grandfathering rule, the exemption will only apply to interest on third party, non-recourse loans and not to related party debt or loans guaranteed by related parties.

These points, together with the inflexibility of an election that can only be revoked (or refreshed, once revoked) after five years, mean the PBIE, as currently conceived, is of quite limited application for more complex infrastructure groups. These will need to fall back on the group ratio or the 30% fixed ratio (watching out for the nasty points mentioned above). Even where the conditions are met, given the long term nature of infrastructure projects and the very real prospect of changes in ownership, it may be difficult for groups to be confident that a PBIE election will always be in the best interests of the group.

There are some specific rules for the real estate sector, including an extension to the PBIE and rules on REITs.

The PBIE does away with the requirement for a ‘public infrastructure asset’ to meet the public benefit test, in circumstances where the asset is a building that forms part of a UK property business and is, or is to be, let on a short-term basis to an unrelated party (‘short-term’ broadly means 50 years or less). This is expected to help commercial property groups; however, given the other PBIE requirements, care must be taken that the property is in vehicles that neither carry on significant other activities nor have subsidiaries outside the UK corporation tax net.

It remains unclear whether the PBIE caters for development-phase properties. The ‘provision’ of public infrastructure assets helpfully includes ‘acquisition, design, construction, conversion, improvement, operation or repair’, although this will only assist where the taxpayer can show that the building is ‘to be let’ to an unrelated party. Grandfathering of old loans is unlikely to benefit, since when the loan was entered into it must have been possible to predict future infrastructure receipts by reference to contracts with (or tendered by) public bodies; this is not expected to apply in most commercial property scenarios.

The property industry raised a concern earlier in the consultation process that the rules could force a REIT, which is obliged to distribute at least 90% of its profits from its exempt property rental business (as they would be calculated for corporation tax purposes) as a property income distribution (PID), to pay excessive PIDs. Broadly speaking, this has been fixed in the latest draft of the legislation by limiting any disallowance to the exempt side of a REIT’s business.

The government has sought to justify its decision not to exempt banking and insurance groups from the scope of the new rules, on the basis that the nature of their businesses is such that they would be expected to be in an overall net interest income position and accordingly they should not be faced with restrictions under the new rules. This has proved to be an over-simplistic assumption, particularly for non-UK headquartered banks and insurers and those groups that carry on a fairly diverse range of businesses within the financial sector. Representative bodies are understood to be in discussion with HMRC in relation to some of the problems.

Ring fenced oil and gas businesses, which are already subject to quite strict limitations on interest deductibility, are exempt from the new rules. Activities outside the ring fence will be subject to the rules in the normal way.

The problems so far identified with the new rules may prove to be the tip of the iceberg. It will be important for HMRC to stay in listening mode, as the regime beds down over the next or year or so, and be prepared to adjust it where necessary, especially given the haste with which such a complex bit of legislation is being ushered in.

The authors thank colleagues Helen Buchanan, Faye Coates and Sam Withnall for their contribution to this article.