FA 2011 ss 47–48 and Schs 12–13 make changes to the interim CFC regime (in advance of the full reform expected in 2012) and introduce an opt-in foreign branch exemption. The key changes to the CFC regime are the introduction of four new exemptions: the trading company exemption; the intellectual property exemption; the alternative de minimis profits exclusion; and the temporary period of grace exemption. The superior and international holding company regime is extended to 2012. Election into the foreign branch exemption regime appears beneficial where there is at least one major low-tax branch and foreign losses are not anticipated. The election is irrevocable and applies to all of a company’s branches, so in deciding whether to elect, a company must carefully consider its overall tax profile. However, the regime is potentially complex and election is not worthwhile just to reduce the compliance burden.

The interim CFC regime changes

The interim CFC regime changesFinance Act 2011 includes legislation to deliver a package of interim improvements to the CFC rules with the aim of making the rules more competitive ahead of full reform in 2012.

It introduces four new exemptions from the CFC regime to apply in addition to the existing rules. These are:

Each of these exemptions is examined below in turn.

The changes will have effect for CFC accounting periods beginning on or after 1 January 2011 (apart for the extension of the transitional rules for holding companies, which will be deemed always to have had effect).

Trading company exemption

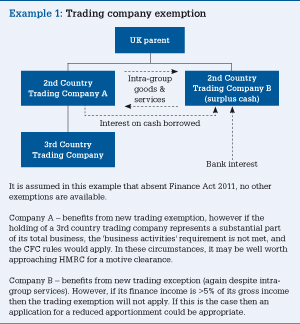

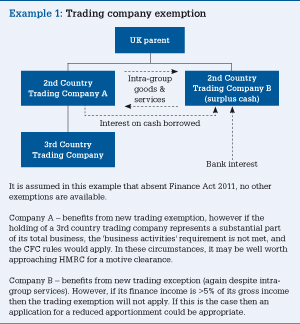

The trading company exemption, will allow companies that carry on intra-group trading activities (such as dealing in goods and the provision of services) to be exempt from a CFC apportionment provided there is limited UK connection.

There are four requirements that need to be met to benefit from the exemption:

1. Throughout the relevant period, the CFC must have a business establishment (this is the same definition as for the existing exempt activities test) in its territory of residence.

2. The CFC’s business must not, at any time in the relevant period:

include to a substantial extent non-exempt activities; or

if it is wholly engaged in banking or similar business, include to a substantial extent non-exempt activities which do not constitute investment business

‘Substantial’ is undefined, but HMRC say up to a maximum of 20% of total business activity is permitted. ‘Non-exempt activities’ consists of investment business plus insurance activities with related persons.

3. The CFC must not have a significant connection with the UK during the relevant period, which it will if Condition A or B below applies.

Condition A: UK connected gross income exceeds 10% of gross income of business unless there are sufficient individuals working for the CFC outside the UK with competence and authority to undertake all, or substantially all of its business; the CFC’s relevant profits do not exceed 10% of relevant operating expenses; and UK-connected gross income does not exceed 50% of gross income of business.

Condition B: UK-connected related-party expenditure exceeds 50% of total related party business expenditure and, the CFC has been involved in a scheme during the period where a main purpose is to achieve a reduction in corporation tax.

4. No more than 5% of the CFC’s gross income must be finance/relevant IP income added together.

A CFC is fully exempt for an accounting period if it meets these requirements. See Example 1.

Intellectual property exemption

The intellectual property exemption will allow companies that hold IP to be exempt from a CFC apportionment provided there is a limited UK connection.

It may apply, for example, where IP is developed or acquired offshore and is then maintained and licensed overseas.

A CFC is fully exempt for an accounting period if it meets the following five requirements:

Both of these exemptions are subject to a new s 751AB which permits a reduced (potentially to nil) CFC apportionment where certain ‘relevant failures’ have prevented the exemptions from applying (subject to the Commissioners for HMRC’s agreement, following an application).

With respect to the trading company exemption, a reduced apportionment may be agreed where one or both of the following ‘relevant failures’ has occurred:

A company must carefully consider its current, future and historic tax profile since the election is irrevocable and is on a company by company, as opposed to a branch by branch, basis |

With respect to the IP exemption, a reduced apportionment may be agreed where the ‘relevant failure’ was to fail to satisfy the finance income requirement.

Practitioners are unlikely to find that these exemptions are widely applicable in practice, but nevertheless, they should be beneficial in a number of cases.

The alternative de minimis profits exclusion

The existing de minimis exclusion, whereby a CFC is exempt if its chargeable profits for a particular accounting period do not exceed £50,000 (proportionately reduced for periods of less than 12 months), is to be retained.

In addition, a new (alternative) de minimis exclusion is to be introduced, whereby a CFC will also be exempt if its ‘relevant profits’ for an accounting period do not exceed £200,000 (proportionately reduced for periods of less than 12 months).

The use of relevant profits is to take account of taxpayers’ complaints that the old system was too complicated. Relevant profits are the profits of the company for that period calculated in accordance with GAAP, disregarding any exempt distributions and any capital gains or losses.

This then is subject to adjustment to take account of any partnership or trust income, as well as transfer pricing adjustments.

The new de minimis exclusion is subject to a variety of anti-avoidance rules to ensure that groups do not take advantage of the new exemption by entering into certain tax planning arrangements such as manipulation of accounting profits, profit fragmentation or mismatch schemes.

The temporary period of grace exemption

The current ‘period of grace’ approach is to be formalised and expanded to allow foreign companies coming under UK control for the first time as a result of an acquisition or re-organisation (including groups migrating or returning to the UK) to be exempt for a period ending 24 months after the end of accounting period in which the acquisition or reorganisation takes place.

Thus, exemption will be available for up to three years.

Despite the seeming simplicity, there are many conditions that need to be met. In particular, the exemption is lost if any ‘relevant transactions’ occur during the exempt period.

It will therefore be important for practitioners to ensure that none of the following ‘relevant transactions’ occur:

Holding companies: extension of transitional provision

The transitional rules, included in FA 2009 Sch 16 Part 2, which allow certain superior and international holding companies to continue to satisfy the exempt activities test are to be extended for an additional 12 months to 1 July 2012 to cover the period to full CFC reform.

This part of the article follows articles on the same topic (see ‘The new branch exemption’ (Tony Beare, Tax Journal dated 16 June 2011 and ‘Foreign branches & financial services’ (Ian Sandles) Tax Journal dated 24 June 2011)) but here the focus is on practical issues in deciding whether to elect for the regime.

Start date of election

Although the legislation is now enacted, most taxpayers cannot apply it immediately as the election only applies for periods commencing after the ‘relevant day’, ie, the date when the next accounting period is expected to begin at the time the election is made. Therefore, the company could change its accounting period to bring forward the start date but only if it already intends to do so when making the election which presumably must disclose this intention.

Compliance burden

Computation of foreign branch profits and losses follows Article 7 (business profits) of the relevant double tax treaty (or the OECD Model if no treaty exists).

The profits or losses to be exempted are then adjusted to the measure of the profits/losses under the credit relief rules and notional capital allowances deducted along with attributable interest expense.

Individual profit components attributable to the foreign branch must also be established (eg, trading profits, capital gains and rental income).

These calculations are complex so taxpayers should not think electing into the regime will reduce the compliance burden over the credit rules, particularly given transitional and anti-diversion rules must also be considered.

Relief for losses

Both profits and losses of foreign branches drop out of account under the branch exemption so there is no relief for foreign branch losses against other eg, UK source profits.

Here, it should be remembered the ongoing profit profile of a branch may fluctuate if it incurs part of the risks and rewards of the business though a low-risk cost-plus foreign branch generally always makes profits.

Transfer pricing is therefore a key issue with close scrutiny by HMRC expected.

Transitional loss rules

Transitional rules prevent effective double relief for branch losses so a company cannot generally benefit from exemption until total branch losses in the six years immediately before the relevant day are matched by subsequent branch profits (losses and profits here exclude capital gains/losses).

The six-year look-back period is extended indefinitely (but not prior to six years from the rules’ start date) where losses exceeding £50 million arose for an accounting period in a foreign branch.

Also the transitional rules are not circumvented where foreign branches are transferred by one UK company to another if the transferor has not elected for exemption.

However, loss-making branches can be streamed so profitable branches benefit sooner from exemption.

The streaming election must be made with the main exemption election and set out the territory to be streamed and the amount of its opening losses.

Reviewing historic profit/losses of each foreign branch is a major compliance burden – difficult if companies have been loss-making generally for a few years with no separate presentation of profits or losses of foreign branches in the corporation tax return.

See examples 2 and 3.

Capital allowances

On entry to the regime, the general rule is a notional disposal value is brought into account of the tax written-down value attributable to the foreign branch.

The notional disposal value forms a separate pool on which, together with further expenditure attributable to the branch, notional capital allowances are computed reducing branch profits that are exempt going forward.

Anti-diversion rule

This rule ensures no advantage in carrying out overseas business through a foreign branch as opposed to a foreign subsidiary that is subject to the CFC rules.

It does not apply if one of three exemptions is met, ie, the branch is not subject to a lower level of tax (using the CFC definition), it has de minimis profits (broadly annual accounting profits up to £200K) or a motive test is met (again based on the CFC equivalent).

However, there is no excluded countries or exempt activities equivalent (the most widely used CFC exemptions).

Therefore, the motive test usually needs to be relied on, at least until next year’s wider CFC reform when any new CFC exemptions will broadly be written into the branch exemption.

Helpfully, HMRC’s draft guidance indicates a foreign branch already carried on in substantially the same way before the exemption should not be caught by the anti-diversion rule.

Also, a pre-existing foreign branch automatically passes the motive test if gross income in the first exempt period does not exceed the previous year by more than 10%, no major change in the nature or conduct of the branch's business occurs and no businesses or assets are transferred into the branch from a non-exempt CFC.

If the anti-diversion rule applies all of the branch’s profits are excluded from exemption unless diversion is identifiable only with UK transactions. Here, only profits from those transactions are excluded.

Which companies should elect in?

A company must carefully consider its current, future and historic tax profile since the election is irrevocable and is on a company by company, as opposed to a branch by branch, basis.

The impact on the accounts tax provision should also be reviewed.

Subject to the transitional loss rules, the election appears beneficial where there is at least one major low-tax branch not within the anti-diversion rule and foreign losses are not anticipated.

However, the election is not worthwhile just to reduce the compliance burden given the regime’s complexity.

Surprisingly, branch exemption seems beneficial for a company with a global trade and trading losses brought forward from its UK operations where it has profitable foreign branches (even if they are high tax). Here the election preserves relief for the tax losses against only UK source profits.

Companies with low tax cost-plus branches also seem to benefit broadly without exception while exemption of capital gains is advantageous.

There is also flexibility if branch operations are located in multiple UK companies so some foreign branches are kept outside the rules.

Alastair Slater, International Tax Senior Manager, KPMG

Choi-Ling Li, Tax Manager, KPMG

FA 2011 ss 47–48 and Schs 12–13 make changes to the interim CFC regime (in advance of the full reform expected in 2012) and introduce an opt-in foreign branch exemption. The key changes to the CFC regime are the introduction of four new exemptions: the trading company exemption; the intellectual property exemption; the alternative de minimis profits exclusion; and the temporary period of grace exemption. The superior and international holding company regime is extended to 2012. Election into the foreign branch exemption regime appears beneficial where there is at least one major low-tax branch and foreign losses are not anticipated. The election is irrevocable and applies to all of a company’s branches, so in deciding whether to elect, a company must carefully consider its overall tax profile. However, the regime is potentially complex and election is not worthwhile just to reduce the compliance burden.

The interim CFC regime changes

The interim CFC regime changesFinance Act 2011 includes legislation to deliver a package of interim improvements to the CFC rules with the aim of making the rules more competitive ahead of full reform in 2012.

It introduces four new exemptions from the CFC regime to apply in addition to the existing rules. These are:

Each of these exemptions is examined below in turn.

The changes will have effect for CFC accounting periods beginning on or after 1 January 2011 (apart for the extension of the transitional rules for holding companies, which will be deemed always to have had effect).

Trading company exemption

The trading company exemption, will allow companies that carry on intra-group trading activities (such as dealing in goods and the provision of services) to be exempt from a CFC apportionment provided there is limited UK connection.

There are four requirements that need to be met to benefit from the exemption:

1. Throughout the relevant period, the CFC must have a business establishment (this is the same definition as for the existing exempt activities test) in its territory of residence.

2. The CFC’s business must not, at any time in the relevant period:

include to a substantial extent non-exempt activities; or

if it is wholly engaged in banking or similar business, include to a substantial extent non-exempt activities which do not constitute investment business

‘Substantial’ is undefined, but HMRC say up to a maximum of 20% of total business activity is permitted. ‘Non-exempt activities’ consists of investment business plus insurance activities with related persons.

3. The CFC must not have a significant connection with the UK during the relevant period, which it will if Condition A or B below applies.

Condition A: UK connected gross income exceeds 10% of gross income of business unless there are sufficient individuals working for the CFC outside the UK with competence and authority to undertake all, or substantially all of its business; the CFC’s relevant profits do not exceed 10% of relevant operating expenses; and UK-connected gross income does not exceed 50% of gross income of business.

Condition B: UK-connected related-party expenditure exceeds 50% of total related party business expenditure and, the CFC has been involved in a scheme during the period where a main purpose is to achieve a reduction in corporation tax.

4. No more than 5% of the CFC’s gross income must be finance/relevant IP income added together.

A CFC is fully exempt for an accounting period if it meets these requirements. See Example 1.

Intellectual property exemption

The intellectual property exemption will allow companies that hold IP to be exempt from a CFC apportionment provided there is a limited UK connection.

It may apply, for example, where IP is developed or acquired offshore and is then maintained and licensed overseas.

A CFC is fully exempt for an accounting period if it meets the following five requirements:

Both of these exemptions are subject to a new s 751AB which permits a reduced (potentially to nil) CFC apportionment where certain ‘relevant failures’ have prevented the exemptions from applying (subject to the Commissioners for HMRC’s agreement, following an application).

With respect to the trading company exemption, a reduced apportionment may be agreed where one or both of the following ‘relevant failures’ has occurred:

A company must carefully consider its current, future and historic tax profile since the election is irrevocable and is on a company by company, as opposed to a branch by branch, basis |

With respect to the IP exemption, a reduced apportionment may be agreed where the ‘relevant failure’ was to fail to satisfy the finance income requirement.

Practitioners are unlikely to find that these exemptions are widely applicable in practice, but nevertheless, they should be beneficial in a number of cases.

The alternative de minimis profits exclusion

The existing de minimis exclusion, whereby a CFC is exempt if its chargeable profits for a particular accounting period do not exceed £50,000 (proportionately reduced for periods of less than 12 months), is to be retained.

In addition, a new (alternative) de minimis exclusion is to be introduced, whereby a CFC will also be exempt if its ‘relevant profits’ for an accounting period do not exceed £200,000 (proportionately reduced for periods of less than 12 months).

The use of relevant profits is to take account of taxpayers’ complaints that the old system was too complicated. Relevant profits are the profits of the company for that period calculated in accordance with GAAP, disregarding any exempt distributions and any capital gains or losses.

This then is subject to adjustment to take account of any partnership or trust income, as well as transfer pricing adjustments.

The new de minimis exclusion is subject to a variety of anti-avoidance rules to ensure that groups do not take advantage of the new exemption by entering into certain tax planning arrangements such as manipulation of accounting profits, profit fragmentation or mismatch schemes.

The temporary period of grace exemption

The current ‘period of grace’ approach is to be formalised and expanded to allow foreign companies coming under UK control for the first time as a result of an acquisition or re-organisation (including groups migrating or returning to the UK) to be exempt for a period ending 24 months after the end of accounting period in which the acquisition or reorganisation takes place.

Thus, exemption will be available for up to three years.

Despite the seeming simplicity, there are many conditions that need to be met. In particular, the exemption is lost if any ‘relevant transactions’ occur during the exempt period.

It will therefore be important for practitioners to ensure that none of the following ‘relevant transactions’ occur:

Holding companies: extension of transitional provision

The transitional rules, included in FA 2009 Sch 16 Part 2, which allow certain superior and international holding companies to continue to satisfy the exempt activities test are to be extended for an additional 12 months to 1 July 2012 to cover the period to full CFC reform.

This part of the article follows articles on the same topic (see ‘The new branch exemption’ (Tony Beare, Tax Journal dated 16 June 2011 and ‘Foreign branches & financial services’ (Ian Sandles) Tax Journal dated 24 June 2011)) but here the focus is on practical issues in deciding whether to elect for the regime.

Start date of election

Although the legislation is now enacted, most taxpayers cannot apply it immediately as the election only applies for periods commencing after the ‘relevant day’, ie, the date when the next accounting period is expected to begin at the time the election is made. Therefore, the company could change its accounting period to bring forward the start date but only if it already intends to do so when making the election which presumably must disclose this intention.

Compliance burden

Computation of foreign branch profits and losses follows Article 7 (business profits) of the relevant double tax treaty (or the OECD Model if no treaty exists).

The profits or losses to be exempted are then adjusted to the measure of the profits/losses under the credit relief rules and notional capital allowances deducted along with attributable interest expense.

Individual profit components attributable to the foreign branch must also be established (eg, trading profits, capital gains and rental income).

These calculations are complex so taxpayers should not think electing into the regime will reduce the compliance burden over the credit rules, particularly given transitional and anti-diversion rules must also be considered.

Relief for losses

Both profits and losses of foreign branches drop out of account under the branch exemption so there is no relief for foreign branch losses against other eg, UK source profits.

Here, it should be remembered the ongoing profit profile of a branch may fluctuate if it incurs part of the risks and rewards of the business though a low-risk cost-plus foreign branch generally always makes profits.

Transfer pricing is therefore a key issue with close scrutiny by HMRC expected.

Transitional loss rules

Transitional rules prevent effective double relief for branch losses so a company cannot generally benefit from exemption until total branch losses in the six years immediately before the relevant day are matched by subsequent branch profits (losses and profits here exclude capital gains/losses).

The six-year look-back period is extended indefinitely (but not prior to six years from the rules’ start date) where losses exceeding £50 million arose for an accounting period in a foreign branch.

Also the transitional rules are not circumvented where foreign branches are transferred by one UK company to another if the transferor has not elected for exemption.

However, loss-making branches can be streamed so profitable branches benefit sooner from exemption.

The streaming election must be made with the main exemption election and set out the territory to be streamed and the amount of its opening losses.

Reviewing historic profit/losses of each foreign branch is a major compliance burden – difficult if companies have been loss-making generally for a few years with no separate presentation of profits or losses of foreign branches in the corporation tax return.

See examples 2 and 3.

Capital allowances

On entry to the regime, the general rule is a notional disposal value is brought into account of the tax written-down value attributable to the foreign branch.

The notional disposal value forms a separate pool on which, together with further expenditure attributable to the branch, notional capital allowances are computed reducing branch profits that are exempt going forward.

Anti-diversion rule

This rule ensures no advantage in carrying out overseas business through a foreign branch as opposed to a foreign subsidiary that is subject to the CFC rules.

It does not apply if one of three exemptions is met, ie, the branch is not subject to a lower level of tax (using the CFC definition), it has de minimis profits (broadly annual accounting profits up to £200K) or a motive test is met (again based on the CFC equivalent).

However, there is no excluded countries or exempt activities equivalent (the most widely used CFC exemptions).

Therefore, the motive test usually needs to be relied on, at least until next year’s wider CFC reform when any new CFC exemptions will broadly be written into the branch exemption.

Helpfully, HMRC’s draft guidance indicates a foreign branch already carried on in substantially the same way before the exemption should not be caught by the anti-diversion rule.

Also, a pre-existing foreign branch automatically passes the motive test if gross income in the first exempt period does not exceed the previous year by more than 10%, no major change in the nature or conduct of the branch's business occurs and no businesses or assets are transferred into the branch from a non-exempt CFC.

If the anti-diversion rule applies all of the branch’s profits are excluded from exemption unless diversion is identifiable only with UK transactions. Here, only profits from those transactions are excluded.

Which companies should elect in?

A company must carefully consider its current, future and historic tax profile since the election is irrevocable and is on a company by company, as opposed to a branch by branch, basis.

The impact on the accounts tax provision should also be reviewed.

Subject to the transitional loss rules, the election appears beneficial where there is at least one major low-tax branch not within the anti-diversion rule and foreign losses are not anticipated.

However, the election is not worthwhile just to reduce the compliance burden given the regime’s complexity.

Surprisingly, branch exemption seems beneficial for a company with a global trade and trading losses brought forward from its UK operations where it has profitable foreign branches (even if they are high tax). Here the election preserves relief for the tax losses against only UK source profits.

Companies with low tax cost-plus branches also seem to benefit broadly without exception while exemption of capital gains is advantageous.

There is also flexibility if branch operations are located in multiple UK companies so some foreign branches are kept outside the rules.

Alastair Slater, International Tax Senior Manager, KPMG

Choi-Ling Li, Tax Manager, KPMG