The bank levy is a completely new tax which comes into force from 1 January 2011. About 30 to 40 banking and building society groups are expected to be affected by it, with an expected yield of about £2.5 billion per year. Finance Act 2011 brings the new tax to life and explains how liability to the levy is calculated. Much of the administrative machinery for the tax is linked to the corporation tax system, but aspects such as double tax relief remain a work in progress.

Finance Act 2011 brings to life the UK’s bank levy, announced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 2010 Budget and the subject of much consultation and detailed design since then.

Finance Act 2011 brings to life the UK’s bank levy, announced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 2010 Budget and the subject of much consultation and detailed design since then.

The bank levy legislation is briefly introduced by the single sentence of s 72, with the vast bulk of the machinery of the levy being contained in Sch 19.

The legislation is complex, in part because of the need to deal with different types of bank and building society groups. In due course the legislation will be supported by regulations, with two sets of draft regulations having been circulated to date.

The first of these details arrangements for double tax relief in connection with the equivalent levy in France, and is likely to be supplemented by further sets of similar regulations as bank levies in other countries continue to take shape.

The second set of draft regulations circulated makes various amendments to the corporation tax instalment payments rules in order to accommodate the levy.

Each of these points is discussed further in this article. The purpose of this article is not to debate the merits or otherwise of this new tax, but rather to focus on how it will operate and what the key issues for affected taxpayers are likely to be.

Having said that, it is worth noting a couple of macroeconomic points before we move on. First, HM Treasury has said that it expects the yield from this new tax to be in the region of £2.5 to £2.6 billion each year from 2011 onwards.

Second, as with all new taxes, and notwithstanding the existence of anti-avoidance rules, there may well be behavioural responses from affected taxpayers which could have wider implications.

HMRC have estimated that about 30 to 40 bank and building society groups will be affected by the levy. Only large groups will be within its scope given that the levy applies to chargeable equity and liabilities (see below) to the extent that they exceed of £20 billion.

Banks with non-sterling functional currencies could find that they move in and out of the scope of the levy even if their business remains at a constant size.

The bank levy will operate as a charge for each period of account, based on the period end balance sheet. The rates for the levy are set at very low percentage rates, but are applied to banks’ balance sheets which are typically very large.

The rates of bank levy have changed twice since the new tax was originally announced. The rates for periods beginning on or after 1 January 2012 will be 0.078% for long-term chargeable equity and liabilities and 0.039% for short-term chargeable equity and liabilities.

There are some differences in rates for 2011, the first year for which the bank levy will apply. This reflects the fact that the 2011 rates were originally expected to be lower but were increased at the time of the 2011 budget announcement in order to counteract the benefit to banks of the lower corporation tax rate.

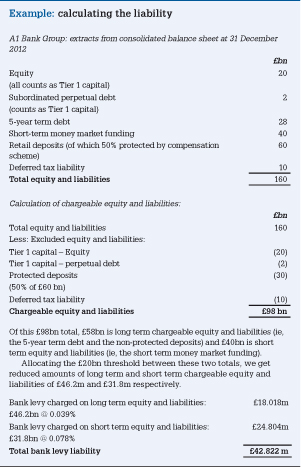

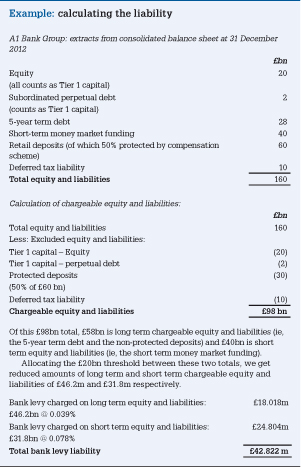

The calculation of chargeable equity and liabilities will vary between different types of group which will be subject to the bank levy, but the broad principles are similar in each case. In each case the starting point will be the total equity and liabilities of the group.

From this total are to be deducted items defined as ‘Excluded’ equity and liabilities. Excluded equity and liabilities will comprise in particular:

HM Treasury also has discretion to specify additional classes of excluded equity and liabilities but has not yet done so.

The total amount of liabilities can be further reduced by detailed rules which allow certain liabilities on bank balance sheets to be netted off against corresponding assets.

Having determined the amount of chargeable equity and liabilities the legislation then sets out in step form a clear approach for calculating the liability to the levy.

The next step is to split the chargeable equity and liabilities total between long-term and short-term chargeable equity and liabilities. In this regard the legislation tells us (not unexpectedly) that all equity is long term.

Less intuitively it also says that non-protected deposits (ie, deposits remaining within the chargeable equity and liabilities total after protected deposits have been excluded) are all to be treated as long term unless the depositor is another financial institution.

Given the run on deposits seen in the Northern Rock case this result seems slightly surprising, but it will be welcome to retail banks nonetheless.

Other liabilities will be treated as long term if they are not required and cannot be required to be repaid within 12 months of the last day of the chargeable period.

The £20 billion threshold is then pro-rated across long-term and short-term equity and liabilities with the bank levy rates then being applied accordingly.

See the Example.

Bank levy is expressly not deductible for corporation tax purposes (although in some cases if the levy can properly be allocated overseas then there may be the possibility of a deduction elsewhere).

More helpfully, recharges in respect of bank levy are also to be disregarded for corporation tax purposes.

The administrative and payment framework for bank levy is linked into the existing mechanisms for corporation tax.

This means, for instance, that payments of the bank levy will be made in quarterly instalments along with corporation tax and that the Senior Accounting Officer requirements will apply to accounting processes supporting the bank levy liability in the same way that they apply to corporation tax.

There is, however, one key difference. While corporation tax remains a tax payable by individual legal entities (albeit subject to group payment arrangements and so on), the liability to bank levy is to be determined on a consolidated basis and is to be payable by a single entity nominated as the ‘representative member’.

Perhaps conscious of the fact that it may not necessarily be clear how much of a particular quarterly tax payment represents a corporation tax liability of the company, and how much the bank levy liability for the wider group, HMRC announced a new scheme of ‘quantification notices’ whereby on or before a particular payment date the representative member must disclose to the group’s CRM how much bank levy is being paid and the period to which it relates.

As indicated previously in this article, HMRC have been in discussion with other tax authorities in Europe with a view to building a framework to reduce the incidence of double taxation with respect to bank levies applied to multinational banking groups.

If the general framework for such relief follows the model proposed for France then the general principle is likely to be the opposite of that which has traditionally applied for income and corporation taxes.

It is envisaged that the primary taxing rights for bank levies will lie with the state of residence rather than the state of source, and that the state of source will give credit for liabilities imposed by the state of residence.

In other words, what we have outlined in the draft regulations circulated by HMRC is a system whereby the UK will grant credit relief to the UK branches of French banks for bank levies assessed by France on UK assets.

At present the draft regulations appear to be defective in that they refer to UK assets being subject to a foreign levy, whereas the UK levy is of course, determined by reference to the liabilities side of the balance sheet.

Doubtless this will be resolved in due course, but it is indicative of the fact that the bank levy is very much new territory for taxpayers and HMRC alike.

Tom Aston, Tax partner, KPMG UK

The bank levy is a completely new tax which comes into force from 1 January 2011. About 30 to 40 banking and building society groups are expected to be affected by it, with an expected yield of about £2.5 billion per year. Finance Act 2011 brings the new tax to life and explains how liability to the levy is calculated. Much of the administrative machinery for the tax is linked to the corporation tax system, but aspects such as double tax relief remain a work in progress.

Finance Act 2011 brings to life the UK’s bank levy, announced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 2010 Budget and the subject of much consultation and detailed design since then.

Finance Act 2011 brings to life the UK’s bank levy, announced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 2010 Budget and the subject of much consultation and detailed design since then.

The bank levy legislation is briefly introduced by the single sentence of s 72, with the vast bulk of the machinery of the levy being contained in Sch 19.

The legislation is complex, in part because of the need to deal with different types of bank and building society groups. In due course the legislation will be supported by regulations, with two sets of draft regulations having been circulated to date.

The first of these details arrangements for double tax relief in connection with the equivalent levy in France, and is likely to be supplemented by further sets of similar regulations as bank levies in other countries continue to take shape.

The second set of draft regulations circulated makes various amendments to the corporation tax instalment payments rules in order to accommodate the levy.

Each of these points is discussed further in this article. The purpose of this article is not to debate the merits or otherwise of this new tax, but rather to focus on how it will operate and what the key issues for affected taxpayers are likely to be.

Having said that, it is worth noting a couple of macroeconomic points before we move on. First, HM Treasury has said that it expects the yield from this new tax to be in the region of £2.5 to £2.6 billion each year from 2011 onwards.

Second, as with all new taxes, and notwithstanding the existence of anti-avoidance rules, there may well be behavioural responses from affected taxpayers which could have wider implications.

HMRC have estimated that about 30 to 40 bank and building society groups will be affected by the levy. Only large groups will be within its scope given that the levy applies to chargeable equity and liabilities (see below) to the extent that they exceed of £20 billion.

Banks with non-sterling functional currencies could find that they move in and out of the scope of the levy even if their business remains at a constant size.

The bank levy will operate as a charge for each period of account, based on the period end balance sheet. The rates for the levy are set at very low percentage rates, but are applied to banks’ balance sheets which are typically very large.

The rates of bank levy have changed twice since the new tax was originally announced. The rates for periods beginning on or after 1 January 2012 will be 0.078% for long-term chargeable equity and liabilities and 0.039% for short-term chargeable equity and liabilities.

There are some differences in rates for 2011, the first year for which the bank levy will apply. This reflects the fact that the 2011 rates were originally expected to be lower but were increased at the time of the 2011 budget announcement in order to counteract the benefit to banks of the lower corporation tax rate.

The calculation of chargeable equity and liabilities will vary between different types of group which will be subject to the bank levy, but the broad principles are similar in each case. In each case the starting point will be the total equity and liabilities of the group.

From this total are to be deducted items defined as ‘Excluded’ equity and liabilities. Excluded equity and liabilities will comprise in particular:

HM Treasury also has discretion to specify additional classes of excluded equity and liabilities but has not yet done so.

The total amount of liabilities can be further reduced by detailed rules which allow certain liabilities on bank balance sheets to be netted off against corresponding assets.

Having determined the amount of chargeable equity and liabilities the legislation then sets out in step form a clear approach for calculating the liability to the levy.

The next step is to split the chargeable equity and liabilities total between long-term and short-term chargeable equity and liabilities. In this regard the legislation tells us (not unexpectedly) that all equity is long term.

Less intuitively it also says that non-protected deposits (ie, deposits remaining within the chargeable equity and liabilities total after protected deposits have been excluded) are all to be treated as long term unless the depositor is another financial institution.

Given the run on deposits seen in the Northern Rock case this result seems slightly surprising, but it will be welcome to retail banks nonetheless.

Other liabilities will be treated as long term if they are not required and cannot be required to be repaid within 12 months of the last day of the chargeable period.

The £20 billion threshold is then pro-rated across long-term and short-term equity and liabilities with the bank levy rates then being applied accordingly.

See the Example.

Bank levy is expressly not deductible for corporation tax purposes (although in some cases if the levy can properly be allocated overseas then there may be the possibility of a deduction elsewhere).

More helpfully, recharges in respect of bank levy are also to be disregarded for corporation tax purposes.

The administrative and payment framework for bank levy is linked into the existing mechanisms for corporation tax.

This means, for instance, that payments of the bank levy will be made in quarterly instalments along with corporation tax and that the Senior Accounting Officer requirements will apply to accounting processes supporting the bank levy liability in the same way that they apply to corporation tax.

There is, however, one key difference. While corporation tax remains a tax payable by individual legal entities (albeit subject to group payment arrangements and so on), the liability to bank levy is to be determined on a consolidated basis and is to be payable by a single entity nominated as the ‘representative member’.

Perhaps conscious of the fact that it may not necessarily be clear how much of a particular quarterly tax payment represents a corporation tax liability of the company, and how much the bank levy liability for the wider group, HMRC announced a new scheme of ‘quantification notices’ whereby on or before a particular payment date the representative member must disclose to the group’s CRM how much bank levy is being paid and the period to which it relates.

As indicated previously in this article, HMRC have been in discussion with other tax authorities in Europe with a view to building a framework to reduce the incidence of double taxation with respect to bank levies applied to multinational banking groups.

If the general framework for such relief follows the model proposed for France then the general principle is likely to be the opposite of that which has traditionally applied for income and corporation taxes.

It is envisaged that the primary taxing rights for bank levies will lie with the state of residence rather than the state of source, and that the state of source will give credit for liabilities imposed by the state of residence.

In other words, what we have outlined in the draft regulations circulated by HMRC is a system whereby the UK will grant credit relief to the UK branches of French banks for bank levies assessed by France on UK assets.

At present the draft regulations appear to be defective in that they refer to UK assets being subject to a foreign levy, whereas the UK levy is of course, determined by reference to the liabilities side of the balance sheet.

Doubtless this will be resolved in due course, but it is indicative of the fact that the bank levy is very much new territory for taxpayers and HMRC alike.

Tom Aston, Tax partner, KPMG UK