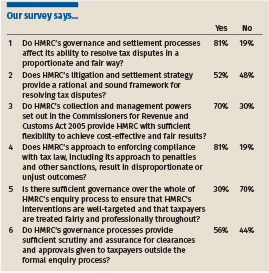

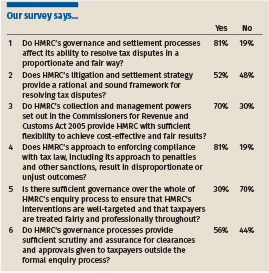

Tax practitioners from more than 20 advisory firms took part in a Tax Journal survey on HMRC’s approach to handling tax enquiries and disputes. The questions were derived from those raised by the Treasury Sub-Committee in its inquiry into this issue. While survey respondents indicated broad support for the framework of HMRC’s powers in CRCA 2005, four fifths of respondents think that: HMRC’s approach to enforcing compliance with tax law results in disproportionate or unjust outcomes; and HMRC’s governance and settlement processes affect the department’s ability to resolve tax disputes in a proportionate and fair way. A large majority believes there is insufficient governance over the whole of HMRC’s enquiry process. Views were more evenly divided on: whether HMRC’s litigation and settlement strategy (LSS) provided a sound framework for resolving disputes; and whether HMRC’s governance processes provide sufficient scrutiny and assurance for clearances and approvals given to taxpayers outside the formal enquiry process.

HMRC officers are taking an ‘all or nothing’ approach to enquiries and disputes that adds to frustration and uncertainty for taxpayers and their advisers, according to a Tax Journal survey of tax practitioners.

HMRC’s litigation and settlement strategy (LSS) lacks necessary flexibility, and officers seem to be influenced by fear of criticism, several respondents suggested.

The House of Commons Treasury Committee announced on 27 March an inquiry in the VAT system, addressing questions regarding the VAT gap, the compliance burden and the impact of Brexit. On the same day, the Treasury Sub-Committee launched an inquiry into the conduct of tax enquiries and the resolution of tax disputes.

In a separate inquiry, the sub-committee will consider steps taken by HMRC to ‘address public concerns around tax avoidance and evasion’, and will examine whether HMRC has the resources, skills and powers needed to bring about ‘a real change in the behaviour of tax dodgers and those who profit by helping them’.

The disputes inquiry will consider whether HMRC practice meets the standards set out in the department’s code of governance for resolving tax disputes, updated in October 2017, which outlines processes that are intended to ensure HMRC handles disputes fairly and in an even-handed manner.

The Tax Journal survey closed on 25 May. It was based on six questions presented by the sub-committee when it invited written submissions to the inquiry by 31 May. (At the time of writing, anyone still wishing to comment was asked to contact the sub-committee.)

Tax Journal asked that only tax practitioners with relevant practical experience took part in the survey and explained that, while responses would be anonymised, the key findings would be shared with the sub-committee. Experts from more than 20 advisory firms including some top ten accountancy firms and leading law firms responded.

Q1. Do HMRC’s governance and settlement processes affect its ability to resolve tax disputes in a proportionate and fair way? Yes 81%, No 19%

More than four in five responses suggested that HMRC’s governance and settlement processes - particularly the LSS - affect HMRC’s ability to resolve disputes fairly and proportionately. HMRC updated its commentary on the LSS, and made some minor changes to the LSS itself, in October 2017.

Several respondents echoed concerns expressed by Ray McCann, partner at Joseph Hage Aaronson, in his inaugural speech as president of the Chartered Institute of Taxation.

‘Even some former HMRC people I know despair at the seeming lack of respect some in HMRC show for taxpayers’ rights and the role of agents,’ McCann said on 22 May. ‘It cannot be acceptable to anyone, including HMRC, when the LSS is used to justify years of delay and an all or nothing approach is applied across the board, often to amounts of tax that anyone would consider low.’

Many taxpayers have been under enquiry for a decade or more, McCann said, adding that ‘we need to keep pressing for a way to get this backlog cleared because the numbers make certain that HMRC will still be at this years from now’.

The LSS is ‘far too rigid’, one respondent said, while another described it as ‘a farce’, and complained that HMRC wastes taxpayers’ money pursuing disputes that it would settle if it took legal advice.

‘On the whole, being driven to resolve disputes fully in accordance with the law is a good thing. However, that leaves a lot to interpretation of what the law says, and HMRC seems reluctant to give up points without a fight,’ one commenter wrote.

Participants complained about the length of time taken to resolve disputes. One wrote of HMRC processes that ‘invite years of ongoing [enquiries] at great cost to the taxpayer’.

While the principles underpinning the ‘collaborative working’ approach are right, HMRC appears to apply them rigidly rather than pragmatically, according to a practitioner who spoke of frustration at the time HMRC takes to go through the processes. Another suggested that timescales, together with HMRC’s ‘consensus-based decision making model’, can make the processes ‘cumbersome, expensive and unpredictable’.

HMRC was also regarded as having too many levels of decision-making, and guilty of ‘a lot of pontification’. One respondent said many HMRC officers were ‘so busy creating an audit trail to show exactly why they reach their decision that they are disproportionately pedantic and drag out the process for a very long time’.

Fear of criticism from both internal and external sources leads HMRC to pursue cases that have insufficient merit, in both very large and ‘low value’ cases, one said.

One participant claimed that, under the LSS, HMRC ‘would rather bankrupt someone and get nothing’ than consider a ‘sub-standard’ offer, particularly in relation to tax avoidance disputes, and added that ‘Eclipse 35’ settlements being pursued by HMRC amount to between 300% and 400% of the tax refunds claimed. ‘This is nonsense, ruins people’s lives and is disproportionate,’ they said.

Lack of access to technical specialists at HMRC can add to frustration felt by taxpayers who feel that powers are stacked against them, according to one response. However, another suggested that despite what some practitioners might say, HMRC’s approach is necessary to ensure consistency among frontline staff.

Time spent in resolving personal tax disputes could be reduced if HMRC provided the taxpayer with evidence of omitted income where the potential loss of tax is less than £1,000, one practitioner said, adding that ‘no HMRC officer seems to be aware of the cost of settling tax disputes’.

A binary, ‘we’re right, the taxpayer is wrong’ approach will result in HMRC taking more cases to the First-tier Tribunal, while some taxpayers will concede rather than risk adverse publicity, one suggested.

Q2. Does HMRC’s litigation and settlement strategy provide a rational and sound framework for resolving tax disputes? Yes 52%, No 48%

While the numbers suggest that opinion was divided on this question, which addressed the LSS specifically, several commenters said there is insufficient flexibility in HMRC’s approach.

There needs to be ‘some flexibility’ and ‘less of a fear of dropping cases’, one respondent said.

The LSS ‘doesn’t allow for a settlement’, said one practitioner. ‘It’s a win or lose in the more complex cases.’

One commenter acknowledged the need for a set of rules on the settlement of tax disputes, for the sake of taxpayer certainty, but argued that HMRC’s ‘all or nothing’ approach dissuades officers from considering that both parties would find commercial sensible. ‘This often results in disproportionate conduct from HMRC and litigation which could and should have been avoided. I believe HMRC needs to adopt a less formulaic approach to resolving tax disputes and approach them in a more commercial manner, considering a ‘meet halfway’ approach,’ they added.

The same respondent’s experience of the alternative dispute resolution process was ‘very positive’, but they suspected that this reflected the facilitator’s push for resolution outside the tribunal rather than a pragmatic approach on the part of the HMRC officers directly involved in the dispute.

Other participants echoed concerns about an alleged ‘all or nothing’ approach:

One respondent complained of insufficient consistency in applying the LSS and ‘a relentless drive to collect revenue regardless of the law’.

Another reported working collaboratively only to find that ‘the HMRC case worker is adversarial’. HMRC had issued FA 2008 Sch 36 (powers to obtain information and documents) notices in several cases ‘where we are cooperating but the information is taking slightly longer than 30 days’. Then HMRC had taken more than six months to reply to that information, they added. ‘Hence many taxpayers feel it is one rule for them and one rule for HMRC in disputes.’

Q3. Do HMRC’s collection and management powers set out in the Commissioners for Revenue and Customs Act 2005 provide HMRC with sufficient flexibility to achieve cost-effective and fair results? Yes 70%, No 30%

Responses indicated broad support for the powers set out in CRCA 2005. One respondent said HMRC’s ‘only stricture’ is the LSS, which is ‘self-imposed’. HMRC needs ‘more political cover against being criticised for dropping cases’, they added.

HMRC has more than enough powers, and the best way to achieve fairer results would be ‘more open dialogue,’ one practitioner said. Another said it was not always clear whether HMRC exercises the discretion afforded by CRCA 2005 s 5 in the most cost-effective and fair way.

Other responses reflected concerns about HMRC’s use of the CRCA powers, rather than the powers themselves:

Q4. Does HMRC’s approach to enforcing compliance with tax law, including its approach to penalties and other sanctions, result in disproportionate or unjust outcomes? Yes ;81%, No 19%

Several readers reported a lack of consistency in HMRC’s approach to imposing penalties. ‘A number of matters I am dealing with are where HMRC’s default position appears to be to impose penalties for deliberate behaviour, without appreciating that the burden of proof is on them to prove the deliberate behaviour,’ one said. ‘I believe penalties are required as a deterrent but more consideration needs to be given to whether they are appropriate in the circumstances and if so, the type of penalty that is applicable,’ they wrote, adding that ‘HMRC is not following its own guidance in a number of cases, which is frustrating’.

The penalties system is ‘a mess’ and is ‘subject to the individual whim of the HMRC officer’, according to one respondent. Others suggested that HMRC:

There is an ‘excessive push to apply penalties, even when they are clearly not appropriate’, according to one practitioner. There have been ‘dreadful examples of HMRC reinterpreting past years’ tax incentives and brutally exploiting hindsight, retrospective legislation and excessive advance tax collection powers’, said another, while one suggested that in the absence of a professional adviser HMRC ‘seems to raise the maximum assessments and penalties it can’.

There was a suggestion that HMRC’s approach may depend on the taxpayer’s size: ‘Much easier for HMRC to penalise small businesses who may not have taken proper advice so acted carelessly. Large corporates have an army of advisers and can only be penalised for obvious implementation errors.’

Q5. Is there sufficient governance over the whole of HMRC’s enquiry process to ensure that HMRC’s interventions are well-targeted and that taxpayers are treated fairly and professionally throughout? Yes 30%, No 70%

One respondent offered ‘a measured yes’ in response to this question but claimed that ‘group think has taken over from application of the law’. Another said interventions seemed to have ‘got a lot better’.

A tax barrister noted an increasing number of cases where HMRC officers have ‘entrenched views and misconceptions’ regarding taxpayers without sufficient evidence to justify the approach. ‘There also appears to be a lack of communication between departments who are enquiring into the same taxpayer, with duplicate requests, and sometimes contradictory communications and information coming from within HMRC. This can be frustrating, administratively burdensome and costly for taxpayers. It would be helpful if there was a more consistent and collaborative approach within HMRC, streamlining the overall process,’ they wrote.

Others noted that:

One reader noted that recent changes to the penalties regime ‘go some way to stopping over-protection of scheme providers’.

Q6. Do HMRC’s governance processes provide sufficient scrutiny and assurance for clearances and approvals given to taxpayers outside the formal enquiry process? Yes 56%, No 44%

This question attracted the fewest comments. An ‘astonishingly swift and precise assessment’ of clearance applications was noted by one reader, who said this was a ‘real welcome improvement’ but also observed an ‘explicitly unhelpful ‘work-to-rule’ in terms of comments or reassurance on facts and analysis’.

The caveats attached to clearance mean the taxpayer can have certainty, another reader noted, ‘provided they disclose everything that is relevant’.

Other observations included:

It is difficult to tell how representative the survey findings are, and participants saying ‘no’ are probably more likely to add a comment. But real concerns about the practical impact of the LSS appear to be widely shared among practising tax professionals, and there is a suggestion that fear of criticism is making HMRC officers wary of settling disputes when they would be justified in doing so.

It will be interesting to see how the Treasury Sub-Committee, chaired by Labour MP John Mann, addresses these issues. Perhaps we will see the focus of public debate move from accusations of ‘sweetheart deals’ to what actually happens when a tax dispute arises.

Tax practitioners from more than 20 advisory firms took part in a Tax Journal survey on HMRC’s approach to handling tax enquiries and disputes. The questions were derived from those raised by the Treasury Sub-Committee in its inquiry into this issue. While survey respondents indicated broad support for the framework of HMRC’s powers in CRCA 2005, four fifths of respondents think that: HMRC’s approach to enforcing compliance with tax law results in disproportionate or unjust outcomes; and HMRC’s governance and settlement processes affect the department’s ability to resolve tax disputes in a proportionate and fair way. A large majority believes there is insufficient governance over the whole of HMRC’s enquiry process. Views were more evenly divided on: whether HMRC’s litigation and settlement strategy (LSS) provided a sound framework for resolving disputes; and whether HMRC’s governance processes provide sufficient scrutiny and assurance for clearances and approvals given to taxpayers outside the formal enquiry process.

HMRC officers are taking an ‘all or nothing’ approach to enquiries and disputes that adds to frustration and uncertainty for taxpayers and their advisers, according to a Tax Journal survey of tax practitioners.

HMRC’s litigation and settlement strategy (LSS) lacks necessary flexibility, and officers seem to be influenced by fear of criticism, several respondents suggested.

The House of Commons Treasury Committee announced on 27 March an inquiry in the VAT system, addressing questions regarding the VAT gap, the compliance burden and the impact of Brexit. On the same day, the Treasury Sub-Committee launched an inquiry into the conduct of tax enquiries and the resolution of tax disputes.

In a separate inquiry, the sub-committee will consider steps taken by HMRC to ‘address public concerns around tax avoidance and evasion’, and will examine whether HMRC has the resources, skills and powers needed to bring about ‘a real change in the behaviour of tax dodgers and those who profit by helping them’.

The disputes inquiry will consider whether HMRC practice meets the standards set out in the department’s code of governance for resolving tax disputes, updated in October 2017, which outlines processes that are intended to ensure HMRC handles disputes fairly and in an even-handed manner.

The Tax Journal survey closed on 25 May. It was based on six questions presented by the sub-committee when it invited written submissions to the inquiry by 31 May. (At the time of writing, anyone still wishing to comment was asked to contact the sub-committee.)

Tax Journal asked that only tax practitioners with relevant practical experience took part in the survey and explained that, while responses would be anonymised, the key findings would be shared with the sub-committee. Experts from more than 20 advisory firms including some top ten accountancy firms and leading law firms responded.

Q1. Do HMRC’s governance and settlement processes affect its ability to resolve tax disputes in a proportionate and fair way? Yes 81%, No 19%

More than four in five responses suggested that HMRC’s governance and settlement processes - particularly the LSS - affect HMRC’s ability to resolve disputes fairly and proportionately. HMRC updated its commentary on the LSS, and made some minor changes to the LSS itself, in October 2017.

Several respondents echoed concerns expressed by Ray McCann, partner at Joseph Hage Aaronson, in his inaugural speech as president of the Chartered Institute of Taxation.

‘Even some former HMRC people I know despair at the seeming lack of respect some in HMRC show for taxpayers’ rights and the role of agents,’ McCann said on 22 May. ‘It cannot be acceptable to anyone, including HMRC, when the LSS is used to justify years of delay and an all or nothing approach is applied across the board, often to amounts of tax that anyone would consider low.’

Many taxpayers have been under enquiry for a decade or more, McCann said, adding that ‘we need to keep pressing for a way to get this backlog cleared because the numbers make certain that HMRC will still be at this years from now’.

The LSS is ‘far too rigid’, one respondent said, while another described it as ‘a farce’, and complained that HMRC wastes taxpayers’ money pursuing disputes that it would settle if it took legal advice.

‘On the whole, being driven to resolve disputes fully in accordance with the law is a good thing. However, that leaves a lot to interpretation of what the law says, and HMRC seems reluctant to give up points without a fight,’ one commenter wrote.

Participants complained about the length of time taken to resolve disputes. One wrote of HMRC processes that ‘invite years of ongoing [enquiries] at great cost to the taxpayer’.

While the principles underpinning the ‘collaborative working’ approach are right, HMRC appears to apply them rigidly rather than pragmatically, according to a practitioner who spoke of frustration at the time HMRC takes to go through the processes. Another suggested that timescales, together with HMRC’s ‘consensus-based decision making model’, can make the processes ‘cumbersome, expensive and unpredictable’.

HMRC was also regarded as having too many levels of decision-making, and guilty of ‘a lot of pontification’. One respondent said many HMRC officers were ‘so busy creating an audit trail to show exactly why they reach their decision that they are disproportionately pedantic and drag out the process for a very long time’.

Fear of criticism from both internal and external sources leads HMRC to pursue cases that have insufficient merit, in both very large and ‘low value’ cases, one said.

One participant claimed that, under the LSS, HMRC ‘would rather bankrupt someone and get nothing’ than consider a ‘sub-standard’ offer, particularly in relation to tax avoidance disputes, and added that ‘Eclipse 35’ settlements being pursued by HMRC amount to between 300% and 400% of the tax refunds claimed. ‘This is nonsense, ruins people’s lives and is disproportionate,’ they said.

Lack of access to technical specialists at HMRC can add to frustration felt by taxpayers who feel that powers are stacked against them, according to one response. However, another suggested that despite what some practitioners might say, HMRC’s approach is necessary to ensure consistency among frontline staff.

Time spent in resolving personal tax disputes could be reduced if HMRC provided the taxpayer with evidence of omitted income where the potential loss of tax is less than £1,000, one practitioner said, adding that ‘no HMRC officer seems to be aware of the cost of settling tax disputes’.

A binary, ‘we’re right, the taxpayer is wrong’ approach will result in HMRC taking more cases to the First-tier Tribunal, while some taxpayers will concede rather than risk adverse publicity, one suggested.

Q2. Does HMRC’s litigation and settlement strategy provide a rational and sound framework for resolving tax disputes? Yes 52%, No 48%

While the numbers suggest that opinion was divided on this question, which addressed the LSS specifically, several commenters said there is insufficient flexibility in HMRC’s approach.

There needs to be ‘some flexibility’ and ‘less of a fear of dropping cases’, one respondent said.

The LSS ‘doesn’t allow for a settlement’, said one practitioner. ‘It’s a win or lose in the more complex cases.’

One commenter acknowledged the need for a set of rules on the settlement of tax disputes, for the sake of taxpayer certainty, but argued that HMRC’s ‘all or nothing’ approach dissuades officers from considering that both parties would find commercial sensible. ‘This often results in disproportionate conduct from HMRC and litigation which could and should have been avoided. I believe HMRC needs to adopt a less formulaic approach to resolving tax disputes and approach them in a more commercial manner, considering a ‘meet halfway’ approach,’ they added.

The same respondent’s experience of the alternative dispute resolution process was ‘very positive’, but they suspected that this reflected the facilitator’s push for resolution outside the tribunal rather than a pragmatic approach on the part of the HMRC officers directly involved in the dispute.

Other participants echoed concerns about an alleged ‘all or nothing’ approach:

One respondent complained of insufficient consistency in applying the LSS and ‘a relentless drive to collect revenue regardless of the law’.

Another reported working collaboratively only to find that ‘the HMRC case worker is adversarial’. HMRC had issued FA 2008 Sch 36 (powers to obtain information and documents) notices in several cases ‘where we are cooperating but the information is taking slightly longer than 30 days’. Then HMRC had taken more than six months to reply to that information, they added. ‘Hence many taxpayers feel it is one rule for them and one rule for HMRC in disputes.’

Q3. Do HMRC’s collection and management powers set out in the Commissioners for Revenue and Customs Act 2005 provide HMRC with sufficient flexibility to achieve cost-effective and fair results? Yes 70%, No 30%

Responses indicated broad support for the powers set out in CRCA 2005. One respondent said HMRC’s ‘only stricture’ is the LSS, which is ‘self-imposed’. HMRC needs ‘more political cover against being criticised for dropping cases’, they added.

HMRC has more than enough powers, and the best way to achieve fairer results would be ‘more open dialogue,’ one practitioner said. Another said it was not always clear whether HMRC exercises the discretion afforded by CRCA 2005 s 5 in the most cost-effective and fair way.

Other responses reflected concerns about HMRC’s use of the CRCA powers, rather than the powers themselves:

Q4. Does HMRC’s approach to enforcing compliance with tax law, including its approach to penalties and other sanctions, result in disproportionate or unjust outcomes? Yes ;81%, No 19%

Several readers reported a lack of consistency in HMRC’s approach to imposing penalties. ‘A number of matters I am dealing with are where HMRC’s default position appears to be to impose penalties for deliberate behaviour, without appreciating that the burden of proof is on them to prove the deliberate behaviour,’ one said. ‘I believe penalties are required as a deterrent but more consideration needs to be given to whether they are appropriate in the circumstances and if so, the type of penalty that is applicable,’ they wrote, adding that ‘HMRC is not following its own guidance in a number of cases, which is frustrating’.

The penalties system is ‘a mess’ and is ‘subject to the individual whim of the HMRC officer’, according to one respondent. Others suggested that HMRC:

There is an ‘excessive push to apply penalties, even when they are clearly not appropriate’, according to one practitioner. There have been ‘dreadful examples of HMRC reinterpreting past years’ tax incentives and brutally exploiting hindsight, retrospective legislation and excessive advance tax collection powers’, said another, while one suggested that in the absence of a professional adviser HMRC ‘seems to raise the maximum assessments and penalties it can’.

There was a suggestion that HMRC’s approach may depend on the taxpayer’s size: ‘Much easier for HMRC to penalise small businesses who may not have taken proper advice so acted carelessly. Large corporates have an army of advisers and can only be penalised for obvious implementation errors.’

Q5. Is there sufficient governance over the whole of HMRC’s enquiry process to ensure that HMRC’s interventions are well-targeted and that taxpayers are treated fairly and professionally throughout? Yes 30%, No 70%

One respondent offered ‘a measured yes’ in response to this question but claimed that ‘group think has taken over from application of the law’. Another said interventions seemed to have ‘got a lot better’.

A tax barrister noted an increasing number of cases where HMRC officers have ‘entrenched views and misconceptions’ regarding taxpayers without sufficient evidence to justify the approach. ‘There also appears to be a lack of communication between departments who are enquiring into the same taxpayer, with duplicate requests, and sometimes contradictory communications and information coming from within HMRC. This can be frustrating, administratively burdensome and costly for taxpayers. It would be helpful if there was a more consistent and collaborative approach within HMRC, streamlining the overall process,’ they wrote.

Others noted that:

One reader noted that recent changes to the penalties regime ‘go some way to stopping over-protection of scheme providers’.

Q6. Do HMRC’s governance processes provide sufficient scrutiny and assurance for clearances and approvals given to taxpayers outside the formal enquiry process? Yes 56%, No 44%

This question attracted the fewest comments. An ‘astonishingly swift and precise assessment’ of clearance applications was noted by one reader, who said this was a ‘real welcome improvement’ but also observed an ‘explicitly unhelpful ‘work-to-rule’ in terms of comments or reassurance on facts and analysis’.

The caveats attached to clearance mean the taxpayer can have certainty, another reader noted, ‘provided they disclose everything that is relevant’.

Other observations included:

It is difficult to tell how representative the survey findings are, and participants saying ‘no’ are probably more likely to add a comment. But real concerns about the practical impact of the LSS appear to be widely shared among practising tax professionals, and there is a suggestion that fear of criticism is making HMRC officers wary of settling disputes when they would be justified in doing so.

It will be interesting to see how the Treasury Sub-Committee, chaired by Labour MP John Mann, addresses these issues. Perhaps we will see the focus of public debate move from accusations of ‘sweetheart deals’ to what actually happens when a tax dispute arises.