Despite action taken by HMRC to reform its assurance procedures, the department remains under pressure to prove that it is doing all it should to collect tax. Trust in HMRC is vital for a good tax system. To improve the current position tax reform proposals need to be based on clear underlying principles. Consultation is now very frequent but it needs to be wider, more comprehensive and better understood. Changes are also needed to the staffing and operation of the revenue authorities. We should welcome, and build upon, good relationships between taxpayers and HMRC, but to provide the necessary assurance, qualified independent experts should be appointed to check on tax settlements as a matter of routine, not only when there is a public outcry. And finally, HMRC should be represented in Parliament by a minister with full accountability, whilst also preserving taxpayer confidentiality.

Judith Freedman (Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation) discusses how the faith of the public, politicians, media, taxpayers and advisers can be restored in HMRC.

A year ago (in the 2016 CTA annual address) I discussed the trust that is at the heart of any good tax system. The general public, politicians, media taxpayers and advisers need to have faith in the revenue authority if our tax system is to continue to operate as it does now, relying heavily on voluntary compliance with tax law. I noted that recent events and tax campaigns had decreased trust in HMRC in relation to the taxation of large business. There have been some cases that have raised concerns (as highlighted in the UK Uncut case [2013] EWHC 1283), but the idea that HMRC was doing ‘sweetheart deals’ should have been dispelled by the National Audit Office’s report in 2012 (Settling large tax disputes, NAO, June 2012) and the subsequent action taken to reform internal procedures and create the post of assurance commissioner. Despite these supposed reassurances, however, when questions were raised about an agreement with Google in 2016, campaigners, politicians and the media showed that they did not trust that the system had resulted in Google paying the tax due. To some extent this was rolled up into the separate, and much larger, question of how much tax should have been due. The upshot was, however, that the Public Account Committee (PAC) once again called for greater transparency about tax settlements (Corporate tax settlements, PAC, February 2016).

Since then, attention may have been diverted from this issue by Brexit and other political events, but the problem remains. The pressure on HMRC to prove that it is doing all it should to collect tax continues. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the changes to internal procedure and the spotlight on settlements are making it increasingly difficult for companies to obtain finality over their tax affairs, but at the same time campaigners and politicians continue to voice concerns, even if they are sometimes based on a failure to separate areas of real concern involving fraud and lack of disclosure from the wider issues of problematic international tax law that is not achieving the current objectives of societies.

It remains important to tackle this issue of trust in our revenue authorities. The complexity of the issues and the law surrounding them, and the fact that, as the PAC pointed out, judgement is often needed to decide tax issues and quantify the amount due, means that simply increasing transparency around taxpayer affairs, even if it could be done, would not solve the problem. Relying on the media, and committees of politicians, NGOs and the public to decide how much tax should be paid cannot be a sustainable or sensible answer. Governments levy tax and the state must provide the means to collect what is due, but the state must also adopt processes that define and convey adequately what tax is due under the law as it stands and reassure the public that this law is being applied even-handedly. If there is dissatisfaction with outcomes when the law is applied, the answer is not to seek to override the law, but to find the best ways to change it, with wide consultation on what is proposed.

In my talk I put forward a modest set of proposals to assist with this problem of trust. Nothing has changed over the past year to change the need to address these points.

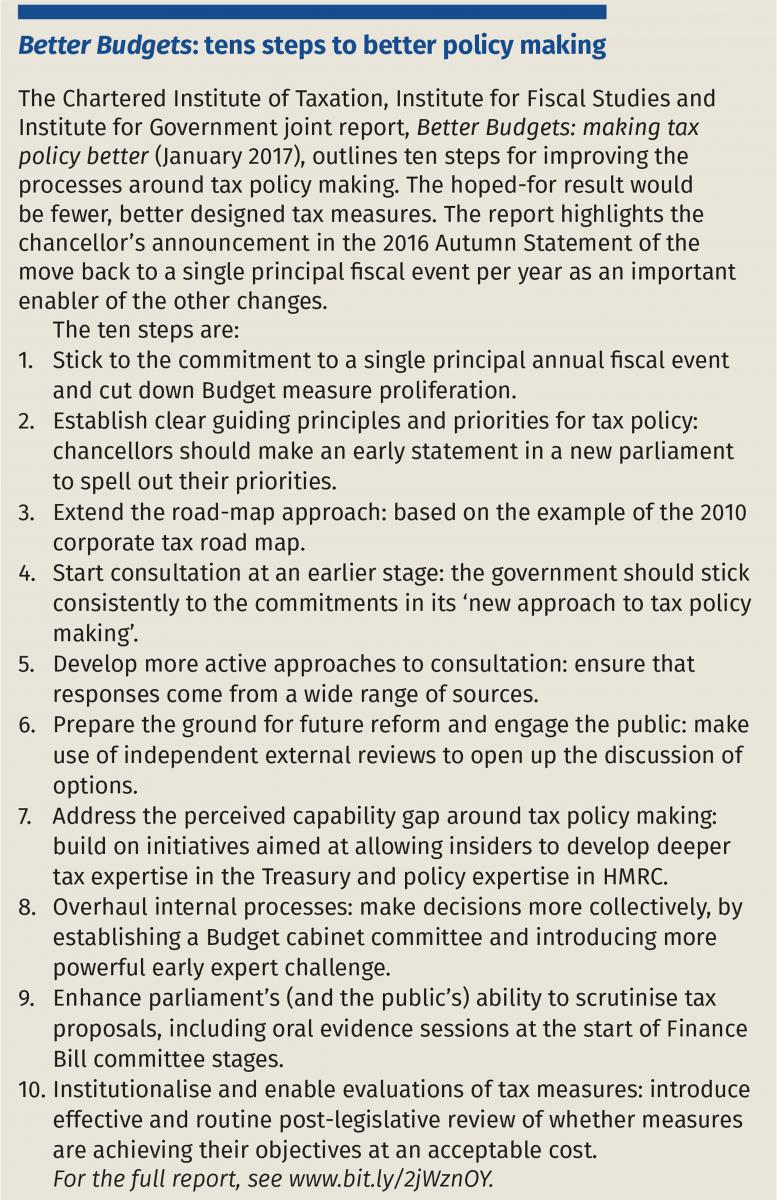

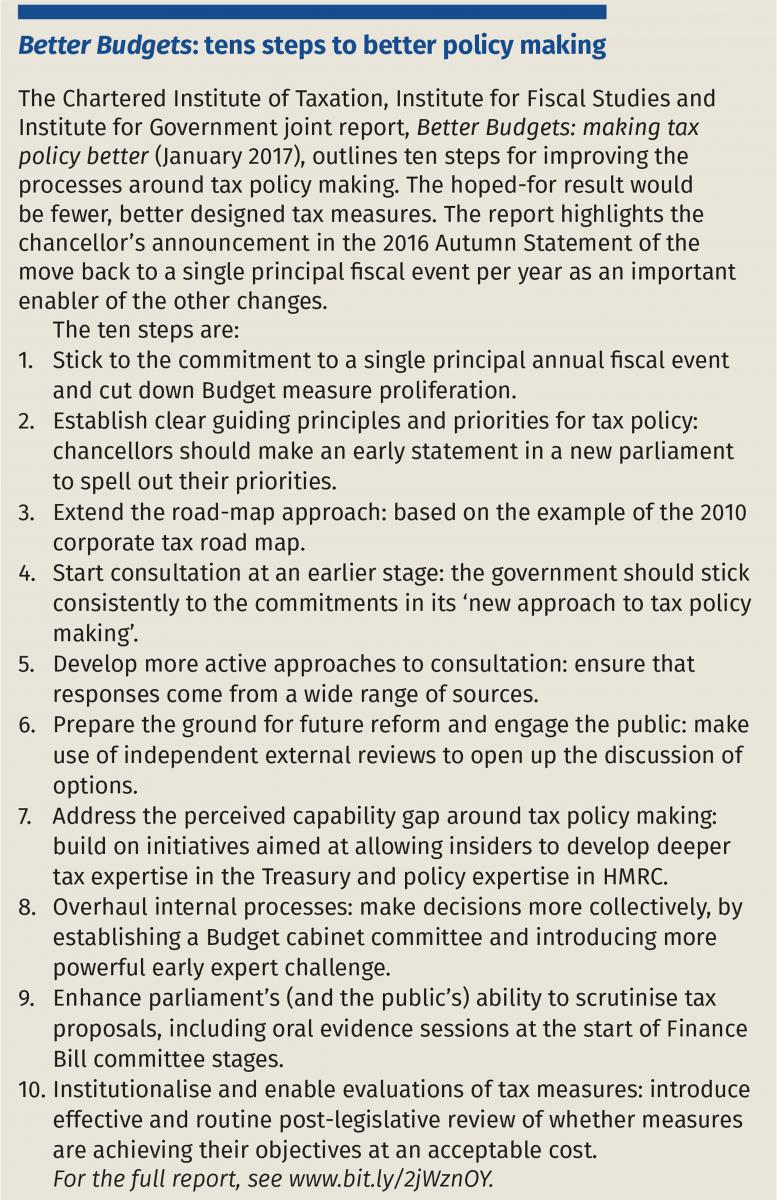

First, tax reform needs much better and less hurried consultation based on clear underlying principles. The 2010 Tax Consultation Framework floods us with consultation documents but does not seem to offer increased engagement beyond a small group of experts. Expert input is vital but may invite (often unfair) mistrust. Better ways need to be found to engage all those affected, not just the experts, through serious informed discussion (not market research). At the same time, HMRC needs to have the expertise to spot self-interested lobbying. Proper consultation takes time and too many changes are still rushed, with consultation taking place after policies have been decided. Discussions should not be constrained by the annual budget cycle. Sometimes this haste is due to the perceived need to respond to public pressure, but proposals made in this way often meet criticism from all sides. Much in this proposal has been reiterated in the recent Better Budgets report (IOG, IFS and CIOT, January 2017). The move to a dingle principal annual fiscal event is welcome, but will not prevent the pressure for annual change.

Second, changes are needed to the staffing and operation of the revenue authorities. Increasing trust requires a well-funded, well-staffed and well-trained revenue authority. This is not just about funding, but about organisation and approach as well as the attitudes of vocal critics. Staff may well work for lower pay than they would in the private sector if they feel their work is worthwhile and valued. Revenue bashing does not help. Lack of institutional memory and failure to understand needs of taxpayers are too frequently apparent in the proposals that come forward and this may be because much experience has been lost from HMRC in recent years, whilst HMT staff now tasked with policy work, excellent though they often are, lack hands on experience and move jobs frequently. Again, these problems are noted in the Better Budgets report, and it seems that some action is being taken to tackle these problems.

Third, we should welcome good relationships between taxpayers and HMRC and build on this. Over recent years, trust between HMRC and many large companies has increased through ‘cooperative compliance’, but, as pointed out above, allegations of ‘cosiness’ now threaten this approach. Yet good relations between taxpayer and the revenue authority can be positive and settlements can be a valuable and efficient way of proceeding to the benefit of society as a whole and not just the taxpayers concerned. It might help if the benefits of personal contact were extended to other taxpayers, many of whom feel very remote from human contact with HMRC. Obviously every taxpayer cannot have a customer relationship manager, but the making tax digital strategy should not be used as an excuse to reduce the workforce in the long term – rather, it is a chance to improve relationships by releasing the workforce from mundane tasks. HMRC’s paper on supporting mid-sized business (February 2017) recognises the need for some human contact through improved call centres and a named contact service in some cases, but still relies very heavily on technology.

Fourth, it has been suggested that details of settlements with taxpayers should be published to allay concerns about ‘sweetheart deals’. This would be neither practical nor useful to the public, who need to be able to trust HMRC to reach good solutions. But the current governance arrangements, centred on the assurance commissioner, rigorous and helpful internally though they may well be, are patently not reassuring the public. Therefore, concerns need to be allayed by appointing suitable qualified independent experts (possibly as part of the NAO or a new external panel) to check on settlements as a matter of routine, not just in response to a crisis.

My fifth recommendation is that HMRC should be represented in Parliament by a minister with full accountability. HMRC needs a stronger voice in Parliament. There is no reason why this should lead to breaches in taxpayer confidentiality; rather, it could help to allay the concerns that are currently leading to calls for reductions in confidentiality about the affairs of corporate taxpayers. Undermining taxpayers confidentiality could hinder the ability of HMRC to manage its central task of collecting the tax due. Proper scrutiny and accountability in order to build trust in HMRC, so that it can get on and do its job, is to be preferred.

Despite action taken by HMRC to reform its assurance procedures, the department remains under pressure to prove that it is doing all it should to collect tax. Trust in HMRC is vital for a good tax system. To improve the current position tax reform proposals need to be based on clear underlying principles. Consultation is now very frequent but it needs to be wider, more comprehensive and better understood. Changes are also needed to the staffing and operation of the revenue authorities. We should welcome, and build upon, good relationships between taxpayers and HMRC, but to provide the necessary assurance, qualified independent experts should be appointed to check on tax settlements as a matter of routine, not only when there is a public outcry. And finally, HMRC should be represented in Parliament by a minister with full accountability, whilst also preserving taxpayer confidentiality.

Judith Freedman (Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation) discusses how the faith of the public, politicians, media, taxpayers and advisers can be restored in HMRC.

A year ago (in the 2016 CTA annual address) I discussed the trust that is at the heart of any good tax system. The general public, politicians, media taxpayers and advisers need to have faith in the revenue authority if our tax system is to continue to operate as it does now, relying heavily on voluntary compliance with tax law. I noted that recent events and tax campaigns had decreased trust in HMRC in relation to the taxation of large business. There have been some cases that have raised concerns (as highlighted in the UK Uncut case [2013] EWHC 1283), but the idea that HMRC was doing ‘sweetheart deals’ should have been dispelled by the National Audit Office’s report in 2012 (Settling large tax disputes, NAO, June 2012) and the subsequent action taken to reform internal procedures and create the post of assurance commissioner. Despite these supposed reassurances, however, when questions were raised about an agreement with Google in 2016, campaigners, politicians and the media showed that they did not trust that the system had resulted in Google paying the tax due. To some extent this was rolled up into the separate, and much larger, question of how much tax should have been due. The upshot was, however, that the Public Account Committee (PAC) once again called for greater transparency about tax settlements (Corporate tax settlements, PAC, February 2016).

Since then, attention may have been diverted from this issue by Brexit and other political events, but the problem remains. The pressure on HMRC to prove that it is doing all it should to collect tax continues. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the changes to internal procedure and the spotlight on settlements are making it increasingly difficult for companies to obtain finality over their tax affairs, but at the same time campaigners and politicians continue to voice concerns, even if they are sometimes based on a failure to separate areas of real concern involving fraud and lack of disclosure from the wider issues of problematic international tax law that is not achieving the current objectives of societies.

It remains important to tackle this issue of trust in our revenue authorities. The complexity of the issues and the law surrounding them, and the fact that, as the PAC pointed out, judgement is often needed to decide tax issues and quantify the amount due, means that simply increasing transparency around taxpayer affairs, even if it could be done, would not solve the problem. Relying on the media, and committees of politicians, NGOs and the public to decide how much tax should be paid cannot be a sustainable or sensible answer. Governments levy tax and the state must provide the means to collect what is due, but the state must also adopt processes that define and convey adequately what tax is due under the law as it stands and reassure the public that this law is being applied even-handedly. If there is dissatisfaction with outcomes when the law is applied, the answer is not to seek to override the law, but to find the best ways to change it, with wide consultation on what is proposed.

In my talk I put forward a modest set of proposals to assist with this problem of trust. Nothing has changed over the past year to change the need to address these points.

First, tax reform needs much better and less hurried consultation based on clear underlying principles. The 2010 Tax Consultation Framework floods us with consultation documents but does not seem to offer increased engagement beyond a small group of experts. Expert input is vital but may invite (often unfair) mistrust. Better ways need to be found to engage all those affected, not just the experts, through serious informed discussion (not market research). At the same time, HMRC needs to have the expertise to spot self-interested lobbying. Proper consultation takes time and too many changes are still rushed, with consultation taking place after policies have been decided. Discussions should not be constrained by the annual budget cycle. Sometimes this haste is due to the perceived need to respond to public pressure, but proposals made in this way often meet criticism from all sides. Much in this proposal has been reiterated in the recent Better Budgets report (IOG, IFS and CIOT, January 2017). The move to a dingle principal annual fiscal event is welcome, but will not prevent the pressure for annual change.

Second, changes are needed to the staffing and operation of the revenue authorities. Increasing trust requires a well-funded, well-staffed and well-trained revenue authority. This is not just about funding, but about organisation and approach as well as the attitudes of vocal critics. Staff may well work for lower pay than they would in the private sector if they feel their work is worthwhile and valued. Revenue bashing does not help. Lack of institutional memory and failure to understand needs of taxpayers are too frequently apparent in the proposals that come forward and this may be because much experience has been lost from HMRC in recent years, whilst HMT staff now tasked with policy work, excellent though they often are, lack hands on experience and move jobs frequently. Again, these problems are noted in the Better Budgets report, and it seems that some action is being taken to tackle these problems.

Third, we should welcome good relationships between taxpayers and HMRC and build on this. Over recent years, trust between HMRC and many large companies has increased through ‘cooperative compliance’, but, as pointed out above, allegations of ‘cosiness’ now threaten this approach. Yet good relations between taxpayer and the revenue authority can be positive and settlements can be a valuable and efficient way of proceeding to the benefit of society as a whole and not just the taxpayers concerned. It might help if the benefits of personal contact were extended to other taxpayers, many of whom feel very remote from human contact with HMRC. Obviously every taxpayer cannot have a customer relationship manager, but the making tax digital strategy should not be used as an excuse to reduce the workforce in the long term – rather, it is a chance to improve relationships by releasing the workforce from mundane tasks. HMRC’s paper on supporting mid-sized business (February 2017) recognises the need for some human contact through improved call centres and a named contact service in some cases, but still relies very heavily on technology.

Fourth, it has been suggested that details of settlements with taxpayers should be published to allay concerns about ‘sweetheart deals’. This would be neither practical nor useful to the public, who need to be able to trust HMRC to reach good solutions. But the current governance arrangements, centred on the assurance commissioner, rigorous and helpful internally though they may well be, are patently not reassuring the public. Therefore, concerns need to be allayed by appointing suitable qualified independent experts (possibly as part of the NAO or a new external panel) to check on settlements as a matter of routine, not just in response to a crisis.

My fifth recommendation is that HMRC should be represented in Parliament by a minister with full accountability. HMRC needs a stronger voice in Parliament. There is no reason why this should lead to breaches in taxpayer confidentiality; rather, it could help to allay the concerns that are currently leading to calls for reductions in confidentiality about the affairs of corporate taxpayers. Undermining taxpayers confidentiality could hinder the ability of HMRC to manage its central task of collecting the tax due. Proper scrutiny and accountability in order to build trust in HMRC, so that it can get on and do its job, is to be preferred.