The UK has proposed an interim digital services tax, to take effect from April 2020. It is a 2% tax on UK revenues derived from social media platforms, search engines or online marketplaces. These categories bring to mind certain big-name multinationals, but the measures could apply more widely. Revenue thresholds are proposed to help small businesses. There is also a safe harbour for loss-making or low profit margin businesses (though the safety net gives an effective tax rate of 80%). There is significant potential for double taxation, and a question mark over consistency with the UK’s international treaty obligations.

The headline announcement in the recent UK Budget was a proposed digital services tax (DST), to take effect from April 2020. The consultation document published on 7 November 2018 (see bit.ly/2PEVKbh) provides further detail and requests views on the design, implementation and administration of the DST by 28 February 2019.

It might be easier to start with what it isn’t. It isn’t an online sales tax or a generalised tax on digital businesses, although it will tax revenues from some types of online activities. It isn’t a solution to the problem of applying OECD principles to profits from digital businesses, although that is the key driver and the long-term goal. It isn’t the ‘Google tax’ (that’s the moniker given to the 2015 diverted profits tax), although Google is one of the main targets. And it isn’t the same as the EU’s proposed DST: this is the UK taking unilateral action.

The DST is a tax on revenue rather than profits. It’s an interim measure to address a perceived problem with the OECD’s international tax framework for dividing up the corporate tax pie between countries. OECD rules give countries the right to tax profits where value is generated but do not (according to some) deal adequately with businesses that derive value from user participation. The international tax community is working on this problem but not fast enough, at least not according to the UK (or the media). As a stop-gap measure, the UK is intending to grab a cool £1.5bn from the biggest players over five years.

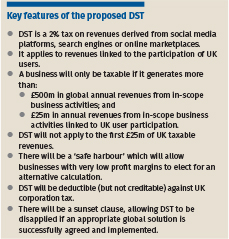

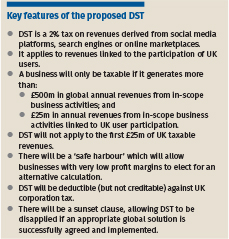

For the key features the DST, see the box below.

The DST is another response to the familiar cry that multinationals, particularly US-headed tech giants, are not paying their fair share. The stated aims are to ensure tax is paid that reflects the value derived from UK users and to address unfair and distortive market outcomes.

It might also be seen as an ‘access to market’ charge for certain types of digital businesses that don’t need boots on the ground. In effect, the UK is treating its user base (and the infrastructure and legal system that enables it) as a national resource that should only be accessed for a price. Whether £1.5bn is the right price is questionable, but the UK is clearly hoping that the tech giants (as the proverbial geese) can spare a few feathers and will be mollified by the promise that the DST is intended to be temporary. The UK might even hope that a global solution can be achieved before the DST takes effect in April 2020 or (more realistically) before the sunset clause requires the UK government to report to Parliament on the continued need for a DST in 2025.

The government claims to be confident that the DST is consistent with its international treaty obligations. The consultation says the tax is not discriminatory, although (as the deductibility examples in Chapter 8 of the consultation show) it may hit international businesses without a UK taxable presence harder than those with UK subsidiaries or branches. The consultation also claims that DST is not a tax on income for double tax treaty purposes because (except where the safe harbour election is made) it taxes gross revenue rather than profit. It’s likely that some groups will want to road test the arguments in Chapter 10 of the consultation that DST is treaty-proof, including the rationale for distinguishing DST from taxes on royalties and technical services fees.

There is no mention in the Consultation of European law prohibitions on indirect and turnover taxes. The European Commission is apparently confident that its own version of the DST is neither an indirect tax nor a turnover tax. Presumably the UK is taking a similar view, or it may be relying on the fact that the DST will not kick in until after Brexit.

The DST legislation will try to define ‘in-scope’ business activities, and impose a tax on third party revenues generated from them. In line with the stated policy drivers, the target is businesses for whom the participation of a user base is a central value creator. That could be a pretty broad net. But the government has identified what it sees as the (only) three categories of business for which this applies:

The three categories immediately bring to mind certain big-name multinationals. The difficulties lie at the margins, and in how one goes about isolating ‘in-scope’ activity from other (closely integrated, but ‘out of-scope’) aspects of a multi-faceted business. There is a whiff of reverse-engineering here; the government knew the particular geese it wanted to pluck, and has drawn the pen to catch them. This is apparent in relation to online gaming, where the issues have not yet been worked through. It is also apparent from the miscellaneous items that are said not to be in-scope, without a clear rationale given the stated policy objectives; including financial and payment services and revenues that a retailer generates from collecting customer data via a loyalty scheme.

All third-party revenues generated from in-scope businesses and linked to the participation of UK users would be subject to the DST – whether from online advertising, subscription fees, sales of data, commissions or otherwise.

Groups with mixed activities will therefore need to attribute their revenue between their in-scope and out-of-scope business lines. That may be a straightforward process for those businesses which happen to structure their reporting lines on this basis but could be a compliance headache for those who do not. They’ll need to come up with a just and reasonable basis of allocation, seemingly without the benefit of any advance clearance mechanism (although taxpayers may hope for some dialogue with HMRC here). Whilst mechanical rules have not been ruled out to assist with that allocation, a one size fits all approach is probably not appropriate here and a just and reasonable override seems likely in any case.

Identifying revenues linked to the participation of UK users will be based on factors such as whether the advert is targeted at UK users, or if payment comes from a UK user. In cross-border transactions (for example, in the context of an online marketplace), the involvement of one UK user will be enough to bring revenues within scope.

How are UK users to be identified? The starting point is where a user is ‘normally resident’ and ‘primarily located’. Although mechanical rules are apparently still being explored, the consultation proposes that businesses will be able to determine user location based on their activities and the way in which they generate revenue. So a search engine may be able to use IP addresses, whereas a marketplace may be able to use payment details or delivery addresses. That flexibility seems reasonable in the circumstances but again risks uncertainty. A clearance mechanism by which taxpayers can confirm with HMRC in advance that their chosen method is acceptable and will not be subject to future challenge would be welcome.

That could also help provide certainty in the challenging cases identified by the consultation, such as where there is contradictory evidence of user location, or where users sign up for or use services whilst travelling outside of the UK. The only guidance offered at this stage is that businesses will need to make yet another just and reasonable apportionment.

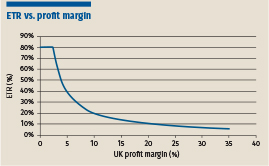

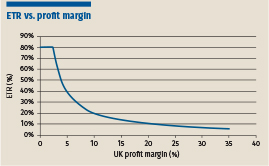

Revenue taxes give rise to distortions and unfair outcomes for loss-making and low-margin businesses. The higher the profit margin, the lower the effective tax rate (ETR) (and vice versa). Whilst a safe harbour has been proposed to deal with this issue, some will be wondering whether it is really that safe.

The safe harbour operates by enabling businesses to make an election to calculate their DST liability according to the following formula rather than by reference to the 2% rate:

UK profit margin x In-scope revenues (less allowance) x X

X is currently expected to be 0.8, with a suggestion in the consultation that it could be set even higher. That means that this election will only be worthwhile making for businesses with a UK profit margin of less than 2.5% (and possibly lower).

The UK profit margin is calculated by reference to the profit made on revenue derived from UK users (wherever earned) so rules will be required to identify allowable costs (including allocations of overheads) for these purposes. The profit margin has a floor of zero, and so it seems that loss-making businesses can effectively elect to be exempt from the DST.

To illustrate how the safe harbour will operate by way of an example:

The impact on ETRs of this safe harbour election (assuming it is made only where the profit margin is less than 2.5%) is illustrated by the graph (below).

The consultation process will consider the duration of elections and whether they should be revocable. It is hoped that the election framework will be flexible enough to cater for loss-making companies so that they are not locked in to paying an 80% ETR once their profit margin exceeds 2.5%.

The DST won’t be creditable against UK corporation tax (possibly this is intended to bolster the UK’s position that the DST is not a tax on income or capital for treaty purposes). Deductions for any DST may be permitted but only if the usual requirements for deductibility of expenses are met: there won’t be any special rules.

In practice, therefore, groups won’t be able to benefit from deductions if they don’t include UK corporation taxpayers. Nor will they benefit if the UK corporation taxpayers in the group don’t receive the revenues subject to the DST (the logic being that the DST won’t then be incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of their trade). This could lead to some fairly arbitrary distinctions based on different group structures, though deductions in other jurisdictions could smooth these out to some extent.

What about double taxation?

The potential for double taxation is significant.

Generally, it appears the risk of multiple UK DST charges should be low (revenues have to be ‘third party’ to be caught so intra-group supplies should not double up charges).

Taxpayers should however expect overlap with foreign equivalents. That’s not confined to cross-border marketplace transactions – differences in how different regimes identify when revenues relate to users in their jurisdictions may result in doubling (or more) of charges. Proposals to negotiate ‘appropriate divisions of taxing rights with the other countries’ to deal with this offer little comfort given the time that will take (and there are obvious drawbacks to distracting attention from negotiation of the global solution).

Taxpayers will also need to be alert for unfavourable interactions with other taxes. As well as corporation tax, there is a real possibility of overlap with other taxes – diverted profits tax and the anticipated tax on offshore receipts in respect of intangible property being obvious examples.

Some level of restructuring may be possible; for example, to reduce the chances of double taxation and/or improve prospects of deductibility. However, two targeted anti-avoidance rules (TAARs) are being considered:

Broadly, the proposal is to follow the corporation tax framework (for corporates at least). Companies would be required to notify if liable to the DST and to self-assess on an annual basis. A quarterly instalment payment regime would also apply.

HMRC also has an eye on how to ensure compliance when the taxpayers may have no UK presence. The proposal is (as becoming more common) joint and several liability for group members. Also on the table is a requirement for group parents to nominate a group reporting company (with the removal of the £25m allowance as a sanction for failure to do so), plus a possible new penalty regime.

There are similarities between the EU and UK proposals. Both propose revenue-based taxes, intended to act as an interim solution from early 2020 pending a comprehensive global solution. They’re not taxes on online activity generally – they’re targeted at similar types of business – and each have worldwide and local revenue thresholds.

However, there are also some key differences. Most obvious is the rate (2% for the UK compared to 3% for the EU) and the lack of safe harbour in EU proposals for loss-makers or those with low profit margins.

The difference in scoping could also be significant. The UK DST would apply to any revenues from the specified types of business, whereas the EU DST would catch specific types of revenue (from sales of online advertising or user data gathered from users’ online activity and from fees for digital intermediary services). Many of the big names will be caught in either case but the scope will differ; for example, sales of online advertising generally are not within scope of the UK proposals but would give rise to the EU DST, whereas subscription fees to use a dating app would be caught in the UK but not the EU. The nexus requirements are also different (increasing risks of double taxation).

All of this will add to the complexity – and the administrative burden – for taxpayers.

Groups (especially, but not just tech multinationals) should be considering their business models and whether they may be in-scope. They should also consider responding to the consultation, particularly where they spot anomalies in scoping and/or compliance issues. Treaty based points could also be made but will probably fall on deaf ears – any mileage there is probably in a challenge down the road.

On a more global level, groups will need to continue monitoring developments. The latest reports suggest EU proposals have hit some bumps in the road and the US has now weighed in, urging the EU to abandon the proposals. Whether they will remains to be seen – but a patchwork of unilateral measures seems inevitable in any case and a comprehensive global solution may be on the (distant) horizon.

The UK has proposed an interim digital services tax, to take effect from April 2020. It is a 2% tax on UK revenues derived from social media platforms, search engines or online marketplaces. These categories bring to mind certain big-name multinationals, but the measures could apply more widely. Revenue thresholds are proposed to help small businesses. There is also a safe harbour for loss-making or low profit margin businesses (though the safety net gives an effective tax rate of 80%). There is significant potential for double taxation, and a question mark over consistency with the UK’s international treaty obligations.

The headline announcement in the recent UK Budget was a proposed digital services tax (DST), to take effect from April 2020. The consultation document published on 7 November 2018 (see bit.ly/2PEVKbh) provides further detail and requests views on the design, implementation and administration of the DST by 28 February 2019.

It might be easier to start with what it isn’t. It isn’t an online sales tax or a generalised tax on digital businesses, although it will tax revenues from some types of online activities. It isn’t a solution to the problem of applying OECD principles to profits from digital businesses, although that is the key driver and the long-term goal. It isn’t the ‘Google tax’ (that’s the moniker given to the 2015 diverted profits tax), although Google is one of the main targets. And it isn’t the same as the EU’s proposed DST: this is the UK taking unilateral action.

The DST is a tax on revenue rather than profits. It’s an interim measure to address a perceived problem with the OECD’s international tax framework for dividing up the corporate tax pie between countries. OECD rules give countries the right to tax profits where value is generated but do not (according to some) deal adequately with businesses that derive value from user participation. The international tax community is working on this problem but not fast enough, at least not according to the UK (or the media). As a stop-gap measure, the UK is intending to grab a cool £1.5bn from the biggest players over five years.

For the key features the DST, see the box below.

The DST is another response to the familiar cry that multinationals, particularly US-headed tech giants, are not paying their fair share. The stated aims are to ensure tax is paid that reflects the value derived from UK users and to address unfair and distortive market outcomes.

It might also be seen as an ‘access to market’ charge for certain types of digital businesses that don’t need boots on the ground. In effect, the UK is treating its user base (and the infrastructure and legal system that enables it) as a national resource that should only be accessed for a price. Whether £1.5bn is the right price is questionable, but the UK is clearly hoping that the tech giants (as the proverbial geese) can spare a few feathers and will be mollified by the promise that the DST is intended to be temporary. The UK might even hope that a global solution can be achieved before the DST takes effect in April 2020 or (more realistically) before the sunset clause requires the UK government to report to Parliament on the continued need for a DST in 2025.

The government claims to be confident that the DST is consistent with its international treaty obligations. The consultation says the tax is not discriminatory, although (as the deductibility examples in Chapter 8 of the consultation show) it may hit international businesses without a UK taxable presence harder than those with UK subsidiaries or branches. The consultation also claims that DST is not a tax on income for double tax treaty purposes because (except where the safe harbour election is made) it taxes gross revenue rather than profit. It’s likely that some groups will want to road test the arguments in Chapter 10 of the consultation that DST is treaty-proof, including the rationale for distinguishing DST from taxes on royalties and technical services fees.

There is no mention in the Consultation of European law prohibitions on indirect and turnover taxes. The European Commission is apparently confident that its own version of the DST is neither an indirect tax nor a turnover tax. Presumably the UK is taking a similar view, or it may be relying on the fact that the DST will not kick in until after Brexit.

The DST legislation will try to define ‘in-scope’ business activities, and impose a tax on third party revenues generated from them. In line with the stated policy drivers, the target is businesses for whom the participation of a user base is a central value creator. That could be a pretty broad net. But the government has identified what it sees as the (only) three categories of business for which this applies:

The three categories immediately bring to mind certain big-name multinationals. The difficulties lie at the margins, and in how one goes about isolating ‘in-scope’ activity from other (closely integrated, but ‘out of-scope’) aspects of a multi-faceted business. There is a whiff of reverse-engineering here; the government knew the particular geese it wanted to pluck, and has drawn the pen to catch them. This is apparent in relation to online gaming, where the issues have not yet been worked through. It is also apparent from the miscellaneous items that are said not to be in-scope, without a clear rationale given the stated policy objectives; including financial and payment services and revenues that a retailer generates from collecting customer data via a loyalty scheme.

All third-party revenues generated from in-scope businesses and linked to the participation of UK users would be subject to the DST – whether from online advertising, subscription fees, sales of data, commissions or otherwise.

Groups with mixed activities will therefore need to attribute their revenue between their in-scope and out-of-scope business lines. That may be a straightforward process for those businesses which happen to structure their reporting lines on this basis but could be a compliance headache for those who do not. They’ll need to come up with a just and reasonable basis of allocation, seemingly without the benefit of any advance clearance mechanism (although taxpayers may hope for some dialogue with HMRC here). Whilst mechanical rules have not been ruled out to assist with that allocation, a one size fits all approach is probably not appropriate here and a just and reasonable override seems likely in any case.

Identifying revenues linked to the participation of UK users will be based on factors such as whether the advert is targeted at UK users, or if payment comes from a UK user. In cross-border transactions (for example, in the context of an online marketplace), the involvement of one UK user will be enough to bring revenues within scope.

How are UK users to be identified? The starting point is where a user is ‘normally resident’ and ‘primarily located’. Although mechanical rules are apparently still being explored, the consultation proposes that businesses will be able to determine user location based on their activities and the way in which they generate revenue. So a search engine may be able to use IP addresses, whereas a marketplace may be able to use payment details or delivery addresses. That flexibility seems reasonable in the circumstances but again risks uncertainty. A clearance mechanism by which taxpayers can confirm with HMRC in advance that their chosen method is acceptable and will not be subject to future challenge would be welcome.

That could also help provide certainty in the challenging cases identified by the consultation, such as where there is contradictory evidence of user location, or where users sign up for or use services whilst travelling outside of the UK. The only guidance offered at this stage is that businesses will need to make yet another just and reasonable apportionment.

Revenue taxes give rise to distortions and unfair outcomes for loss-making and low-margin businesses. The higher the profit margin, the lower the effective tax rate (ETR) (and vice versa). Whilst a safe harbour has been proposed to deal with this issue, some will be wondering whether it is really that safe.

The safe harbour operates by enabling businesses to make an election to calculate their DST liability according to the following formula rather than by reference to the 2% rate:

UK profit margin x In-scope revenues (less allowance) x X

X is currently expected to be 0.8, with a suggestion in the consultation that it could be set even higher. That means that this election will only be worthwhile making for businesses with a UK profit margin of less than 2.5% (and possibly lower).

The UK profit margin is calculated by reference to the profit made on revenue derived from UK users (wherever earned) so rules will be required to identify allowable costs (including allocations of overheads) for these purposes. The profit margin has a floor of zero, and so it seems that loss-making businesses can effectively elect to be exempt from the DST.

To illustrate how the safe harbour will operate by way of an example:

The impact on ETRs of this safe harbour election (assuming it is made only where the profit margin is less than 2.5%) is illustrated by the graph (below).

The consultation process will consider the duration of elections and whether they should be revocable. It is hoped that the election framework will be flexible enough to cater for loss-making companies so that they are not locked in to paying an 80% ETR once their profit margin exceeds 2.5%.

The DST won’t be creditable against UK corporation tax (possibly this is intended to bolster the UK’s position that the DST is not a tax on income or capital for treaty purposes). Deductions for any DST may be permitted but only if the usual requirements for deductibility of expenses are met: there won’t be any special rules.

In practice, therefore, groups won’t be able to benefit from deductions if they don’t include UK corporation taxpayers. Nor will they benefit if the UK corporation taxpayers in the group don’t receive the revenues subject to the DST (the logic being that the DST won’t then be incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of their trade). This could lead to some fairly arbitrary distinctions based on different group structures, though deductions in other jurisdictions could smooth these out to some extent.

What about double taxation?

The potential for double taxation is significant.

Generally, it appears the risk of multiple UK DST charges should be low (revenues have to be ‘third party’ to be caught so intra-group supplies should not double up charges).

Taxpayers should however expect overlap with foreign equivalents. That’s not confined to cross-border marketplace transactions – differences in how different regimes identify when revenues relate to users in their jurisdictions may result in doubling (or more) of charges. Proposals to negotiate ‘appropriate divisions of taxing rights with the other countries’ to deal with this offer little comfort given the time that will take (and there are obvious drawbacks to distracting attention from negotiation of the global solution).

Taxpayers will also need to be alert for unfavourable interactions with other taxes. As well as corporation tax, there is a real possibility of overlap with other taxes – diverted profits tax and the anticipated tax on offshore receipts in respect of intangible property being obvious examples.

Some level of restructuring may be possible; for example, to reduce the chances of double taxation and/or improve prospects of deductibility. However, two targeted anti-avoidance rules (TAARs) are being considered:

Broadly, the proposal is to follow the corporation tax framework (for corporates at least). Companies would be required to notify if liable to the DST and to self-assess on an annual basis. A quarterly instalment payment regime would also apply.

HMRC also has an eye on how to ensure compliance when the taxpayers may have no UK presence. The proposal is (as becoming more common) joint and several liability for group members. Also on the table is a requirement for group parents to nominate a group reporting company (with the removal of the £25m allowance as a sanction for failure to do so), plus a possible new penalty regime.

There are similarities between the EU and UK proposals. Both propose revenue-based taxes, intended to act as an interim solution from early 2020 pending a comprehensive global solution. They’re not taxes on online activity generally – they’re targeted at similar types of business – and each have worldwide and local revenue thresholds.

However, there are also some key differences. Most obvious is the rate (2% for the UK compared to 3% for the EU) and the lack of safe harbour in EU proposals for loss-makers or those with low profit margins.

The difference in scoping could also be significant. The UK DST would apply to any revenues from the specified types of business, whereas the EU DST would catch specific types of revenue (from sales of online advertising or user data gathered from users’ online activity and from fees for digital intermediary services). Many of the big names will be caught in either case but the scope will differ; for example, sales of online advertising generally are not within scope of the UK proposals but would give rise to the EU DST, whereas subscription fees to use a dating app would be caught in the UK but not the EU. The nexus requirements are also different (increasing risks of double taxation).

All of this will add to the complexity – and the administrative burden – for taxpayers.

Groups (especially, but not just tech multinationals) should be considering their business models and whether they may be in-scope. They should also consider responding to the consultation, particularly where they spot anomalies in scoping and/or compliance issues. Treaty based points could also be made but will probably fall on deaf ears – any mileage there is probably in a challenge down the road.

On a more global level, groups will need to continue monitoring developments. The latest reports suggest EU proposals have hit some bumps in the road and the US has now weighed in, urging the EU to abandon the proposals. Whether they will remains to be seen – but a patchwork of unilateral measures seems inevitable in any case and a comprehensive global solution may be on the (distant) horizon.